What is radioactivity?

Radioactive minerals are minerals that contain elements which emit radioactive radiation as they decay. An atom’s nucleus consists of protons and neutrons. Ideally, the number of protons and neutrons is balanced. When this balance is disrupted, the nucleus becomes unstable.

In an unstable nucleus, this imbalance leads to nuclear decay, a process in which the atom attempts to regain stability. During this decay, energy is released in the form of ionising radiation, also known as radioactivity. This is a natural process, occurring constantly all around us.

Because of past tragedies involving atomic bombs and nuclear power plant accidents, many people associate radioactivity with danger. And rightly so: we know that excessive exposure to radiation can harm the body and even cause serious illness. Yet, radioactivity also has valuable applications in modern life. The most well-known examples include X-rays in medical imaging and radiation therapy in cancer treatment.

Types of Radioactive radiation

There are several forms of radioactive decay, but the three most common types of ionising radiation are:

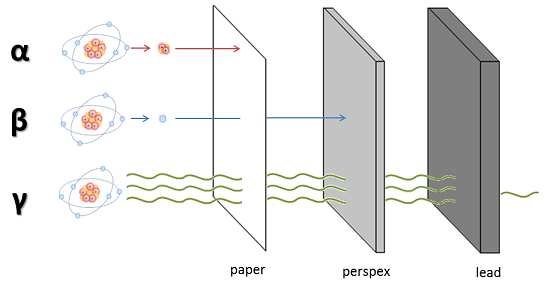

Alpha Radiation (α)

In this process, an atom emits two protons and two neutrons, essentially a helium-4 nucleus. These are relatively large and heavy particles that can be stopped easily, even a sheet of paper is enough to block them. Alpha radiation is the most common form, and although it’s harmless outside the body, it can be dangerous if inhaled or ingested, as it then comes into direct contact with sensitive internal tissues.

Beta Radiation (β)

This type of radiation occurs when an atom emits an electron or a positron (the electron’s antimatter equivalent). These are much smaller particles than alpha particles, but still carry enough energy to pose a risk. They can be blocked by a thick book, a wall, a sheet of aluminium, or heavy-duty plastic such as thick plexiglass. Sufficient distance can also reduce exposure.

Gamma Radiation (γ)

Gamma radiation is not made up of particles but consists of high-energy electromagnetic waves, or photons. The classification as gamma radiation depends on the energy level of the photons, measured in electron volts (eV). Below gamma rays in the spectrum are X-rays, and beneath those lies ultraviolet light.

Gamma rays are less ionising than alpha particles but are much harder to block. They can penetrate deep into materials, including the human body. Protection requires dense materials such as lead, concrete, or water. Long-term or repeated exposure to gamma radiation can cause serious biological damage.

An atom cannot keep decaying indefinitely. Eventually, the nucleus becomes stable again, and the material stops being radioactive.

The time it takes for half of a radioactive substance to decay is called its half-life. This value gives us an indication of how long a material remains radioactive. Some elements have extremely long half-lives, remaining radioactive for thousands or even millions of years, while others decay within seconds or minutes.

How can you recognise radioactive minerals?

Most minerals classified as radioactive on paper are only mildly radioactive in practice. The radiation they emit generally does not travel far and is often easily blocked (see the earlier explanation on alpha, beta, and gamma radiation). Simply storing them in a sealed container, avoiding direct handling, and keeping them at a reasonable distance is usually enough to minimise any risk.

But of course, it helps to know which substances are radioactive in the first place. Not every mineral that contains a radioactive element is equally radioactive. Many elements can exist in unstable, radioactive isotopic forms, while others are naturally stable.

There are 37 elements that have no stable isotopes at all, meaning they are inherently radioactive. However, most of these are either synthetic or occur very rarely in nature. The majority of naturally radioactive minerals owe their activity to the presence of uranium (U) and thorium (Th). These symbols can often be spotted in a mineral’s chemical formula

Examples of Uranium-bearing minerals:

Torbernite

Uraninite (also known as pitchblende)

Autunite

Cuprosklodowskite

Davidite

Examples of Thorium-bearing minerals:

Monazite

Thorite

Aeschynite

Yttrialite

There is another radioactive element commonly found in uranium-bearing minerals: radium. However, radium typically does not appear in a mineral’s chemical formula, as it is formed as a decay product rather than being part of the original mineral composition. There is only one known mineral in which radium is part of the formula: radian baryte (also known as radiobarite).

Are radioactive minerals common in collections?

In most standard and commonly traded collector’s minerals, the amount of radioactive material present is so low that it poses no significant health risk. However, if you begin collecting more specialised or raw mineral specimens, the chance of encountering radioactive minerals does increase

That’s why it is always wise to check the chemical formula of a mineral before adding it to your collection. If you spot uranium (U) or thorium (Th) in the formula, you should exercise caution and handle the specimen appropriately.

It’s also sensible to consider the origin of a specimen. If you collect minerals from regions or mines known to produce uranium or thorium, it is advisable to scan even non-radioactive minerals from those localities with a Geiger counter. Sometimes, associated minerals that appear harmless on paper may still be contaminated or intergrown with radioactive substances.

It’s not always easy to tell whether a specimen includes a trace of a radioactive component, especially in complex or mixed samples. When in doubt, a radiation check can provide peace of mind.

Handling radioactive minerals safely

A radioactive mineral is not a pocket stone or something to be handled casually. It should not be added to your collection without proper knowledge and care. That said, radioactive specimens can make fascinating additions to a collection, provided you understand what you’re acquiring and how to store it safely. Please bear in mind that not all countries allow you to own radioactive minerals! Selling, buying or swapping radioactive minerals and sending them abroad must be done with great care and consideration of custom rules and regulations. Sending a radioactive specimen to another country can be a tricky business.

Despite the generally low radiation levels emitted by most radioactive minerals, precautions are always necessary. These minerals should never be stored in your living room or bedroom, as some specimens may emit higher levels of radiation than expected. This can be measured with a Geiger counter. To ensure that radiation exposure remains harmless, many collectors choose to store higher-emission or gamma-emitting specimens in a lead container. Lead is effective in blocking all forms of radiation.

Radon gas: A hidden risk

A greater danger lies in radon gas, a by-product of radioactive decay. This gas can accumulate in sealed containers where radioactive minerals are stored. It is important to avoid inhaling this gas. Always open specimen boxes in a well-ventilated area, and never directly above your face.

Dust and particle contamination

Another risk is the inhalation or ingestion of fine particles or dust from a radioactive specimen. Even microscopic crumbs can pose long-term health risks if they enter the body.

To minimise this risk:

– Store radioactive specimens in sealed containers

– Clearly label each item to indicate its radioactive nature: this protects both you and others who may handle it

– Always keep radioactive specimens out of reach of children

Never wear radioactive minerals as jewellery! It may go without saying, but radioactive minerals should never be worn as jewellery. Prolonged contact with the skin can be harmful over time, even with low-emission specimens.

Natural radiation

Radioactive radiation occurs naturally all around us. The main sources are the rocks beneath our feet, seawater, and radiation that reaches us from outer space.

Cosmic radiation

Cosmic radiation originates from the Sun and from the wider universe. There is little we can do to avoid it. The higher you are, for example, in the mountains or in an aeroplane, the more cosmic radiation you are exposed to.

Terrestrial radiation

Terrestrial (earth-based) radiation mainly arises from the decay of radioactive elements in the ground, particularly uranium, thorium, and radium. This may sound alarming, but, all rocks and minerals contain these elements in minimal amounts, known as trace elements. These quantities are measured in parts per million (ppm), that is, the number of atoms of one element per million atoms in total.

For uranium, the global average is about 2.8 ppm, meaning that out of every million atoms, 2.8 are uranium. That might sound negligible, but it is in fact considerably higher than, for example, gold, which averages only 0.005 ppm.

Some rocks contain more uranium than others. Granite, for instance, has an above-average uranium content. Much of Europe is underlain by granite, which means that a large part of the continent naturally emits more radiation than areas with other types of bedrock.

As uranium decays, it releases radon gas, a naturally radioactive gas that can escape from granite. This is not a problem if you have a few granite specimens in your mineral collection or if you go walking over a granite hill. However, if your house is built directly on granite and you live there continuously, the situation becomes more significant.

Another contributor to background radiation is potassium-40, a mildly radioactive isotope of potassium. Though only weakly radioactive, its abundance in nature means that it still contributes noticeably to the Earth’s natural background radiation.

Measuring radioactivity

Radioactivity can be measured in several units. One of the most common is the becquerel (Bq), which indicates the number of atomic nuclei that decay per second. The higher the number of becquerels, the greater the rate of decay, and thus the higher the radiation level.

When referring to radon gas, the concentration is measured in becquerels per cubic metre (Bq/m³). The unit is named after Henri Becquerel, who discovered radioactivity, and it is the internationally recognised standard for measuring it.

Another important unit is the sievert (Sv), or more commonly, the millisievert (mSv). This unit measures the biological effect of radiation, representing the dose to which a person is exposed over a certain period of time.

Radon and the home environment

Fortunately, radon has a relatively short half-life. Within about three to four days, it decays into less harmful elements. The key is to prevent it from building up indoors if your home is in an area where the soil releases radon gas.

Houses with raised radon levels can be made safer quite easily by installing proper floor insulation, adequate ventilation, and sealing cracks or gaps around pipes and cables entering from the ground. In several parts of the world, it is standard practice to install systems that vent radon gas from cellars and crawl spaces. Continuous ventilation also helps to reduce concentrations effectively.

Natural radiation in Europe

Across Europe, areas with high levels of natural radiation include parts of France, the Czech Republic, south-west England, and Scandinavia. In some regions, such as Cornwall in England, the government has introduced measures to help protect homes from radon exposure. In Cornwall, the gas originates from granite, which dominates the local geology.

Prolonged exposure to high concentrations of radon gas can increase the risk of lung cancer. Similarly, parts of the Czech Republic and Scandinavia experience elevated natural radiation due to uranium-rich rocks and deposits. In some of these areas, uranium mining was historically an important industry.

Everyday exposure

Now for a practical thought… how many of us have granite worktops in our kitchens? You might be surprised to learn that these surfaces also emit a very small amount of radiation. But don’t rush to tear out your kitchen just yet!

Although alarming reports have occasionally appeared in the media, scientific studies have shown that granite countertops pose no significant risk. The only potential concern would be a very small, poorly ventilated kitchen containing a large and thick granite surface, kept sealed for weeks at a time, a highly unlikely scenario.

Human-made sources of radiation

In addition to natural radiation, we are also exposed daily to artificial sources of radiation, those created by human activity. These include building materials, medical treatments, and nuclear waste, among others.

The use of radioactive substances in history

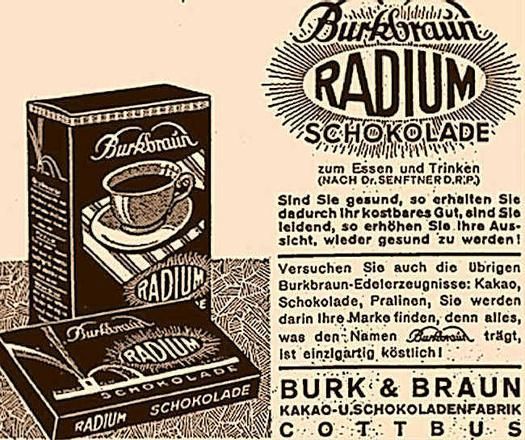

When radioactivity was first discovered, it was not immediately regarded as something hazardous. On the contrary, many believed it could have beneficial effects on human health. One element in particular, radium, discovered in 1898 by Marie Curie, was seen as having great potential for improving wellbeing.

As a result, radium was added to a wide range of everyday products. There was radium-infused water for therapeutic baths and even for drinking. People could purchase radium pills, radium bread, radium chocolate, radium lotion, radium lipstick, radium toothpaste, radium butter, radium shampoo, and rejuvenation tonics containing radium, among other things.

Astonishingly, there was even a brand of condoms that advertised itself as offering ‘radium’ protection. Fortunately, these particular products did not actually contain any radioactive material.

Radithor and the dangers of radioactive substances

A well-known brand of ‘medicinal’ radioactive water was Radithor. It was marketed with numerous misleading claims, and its manufacturer even dubbed it the ‘Perpetual Sunshine’. One famous socialite, sportsman, and lawyer from the early 20th century, Ebenezer Byers, consumed such large quantities of this drink that he ultimately died from multiple tumours. When his body was exhumed more than 30 years after his death, it still emitted extremely high levels of radiation. At one point, he was reportedly drinking as many as three bottles a day, and this continued for many years.

Because radium paint glowed in the dark, it was commonly used on the hands of clocks, watches, and navigation instruments for aeroplanes. This radium paint was applied with very fine brushes. The task was often performed by young women who, to keep the tips of their brushes sharp, would moisten the brush tips with their lips and shape them with their mouths. Over time, many of these women developed severe illnesses caused by exposure to the radioactive paint. Many fell gravely ill and died. These women became known as the ‘Radium Girls’.

The US Radium Corporation, where these women worked, initially refused to accept any responsibility and denied that the women’s illnesses were caused by their work. They even attempted to discredit the women by accusing them of having contracted syphilis, tarnishing their reputations. After a prolonged struggle and legal battles, the women were finally awarded compensation and their story became public knowledge. Despite this, radium-containing paint was not banned until the 1970s.|

For this reason, it is advisable to be cautious with old timepieces or instruments used in airplanes or machinery that have hands, numeralsor other parts that ‘glow in the dark’, as there is a strong chance that such paint contains radium.

Uranium and its industrial uses

Uranium also found its way into the manufacturing of everyday objects. Particularly popular was the greenish-yellow uranium glass. This is glass to which a small percentage of uranium had been added. When exposed to ultraviolet (UV) light, the glass would glow a striking green colour. This type of glass was produced well into the 20th century and can very likely still be found in many display cabinets, antique shops, and charity stores. Most of this glass is harmless due to the very low uranium content. However, there are examples of glass containing significantly higher levels of uranium. Certain types of ceramic glazing is another thing that can be slightly radioactive.

Today, we are much more aware of the risks associated with radioactive materials. Nevertheless, there remain many useful applications for them. Most notably, their role in the medical field, particularly in the treatment of cancer, is well recognised. We are also all aware of their importance in generating energy. However, radioactive materials also have a darker side, which is especially pertinent in these uncertain times, namely, their use in nuclear weapons, the devastating power of which we hope will never be unleashed.