Is fluorite toxic?

A common belief is that fluorite is toxic when placed in water. Fluorite is a popular and widespread mineral, composed largely of, as the name suggests, fluorine. Fluorine is a chemical element that we already ingest in small amounts through drinking water and toothpaste. While fluorine itself is indeed toxic, it is generally harmless in very small quantities.

Fortunately, in fluorite, the chemical bond between calcium and fluorine is very strong, making the mineral chemically stable and non-toxic. Even if fluorite is placed in drinking water (which is not recommended for other reasons), it poses no realistic risk of fluorine poisoning. However, care should be taken not to expose fluorite to acids, as this can release corrosive substances.

Fluorine in other minerals

This does not mean that all fluorine-bearing minerals are safe. One of the riskier minerals actually contains fluorine: villiaumite. Villiaumite belongs to the halite group and has the chemical formula NaF (sodium fluoride). Unlike its close relative rock salt (halite), villiaumite is not edible and must never be licked or handled casually. It is highly soluble in water, and the released fluoride makes it poisonous.

If you own a specimen of villiaumite, it should be kept sealed, protected from moisture and humidity. Avoid handling it frequently, and if you do hold it, don’t get sweaty hands and wash your hands afterwards.

Pyrite disease risks

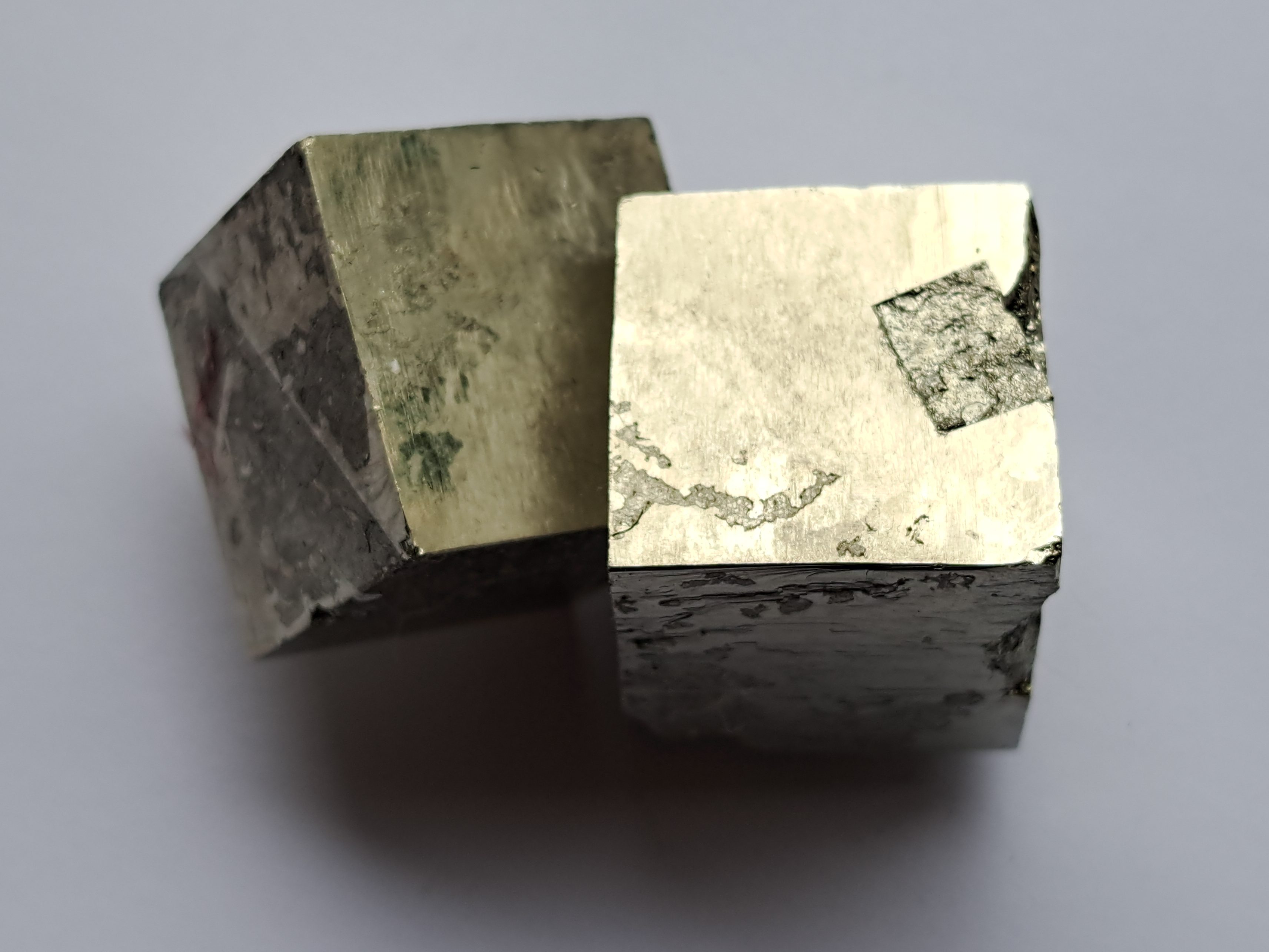

Pyrite is often referred to as “fool’s gold” because of its metallic, golden sheen. In the past, it was sometimes mistaken for real gold and even sold as such. Pyrite is a common mineral; it occurs both independently and in association with other minerals, and sometimes replaces organic material during fossilisation. In fact, some fossils consist almost entirely of pyrite.

The name pyrite derives from the Greek word pyr, meaning fire, due to its ability to produce sparks when struck against another stone (such as flint). Occasionally, pyrite forms beautiful, perfectly shaped cubic crystals, such as those from the famous Spanish locality of Navajún. However, it can also occur in other crystal habits, though the crystal structure always remains cubic. A characteristic feature of pyrite cubes is the fine striations on each face, which are oriented at right angles to those on adjacent faces.

Stability and pyrite decay

Pyrite itself is generally considered a low-risk mineral in terms of toxicity. However, when exposed to moisture and oxygen, it begins to oxidise. This can result in harmless rust formation, but also in a process known as pyrite decay or pyrite disease.

Moisture does not only mean liquid water, high humidity alone can be damaging. During oxidation, iron oxides and sulphates are produced, and the surface of the mineral may develop a white or yellow powdery coating. You may also notice a sulphurous smell as the mineral slowly disintegrates into a yellowish-white powder, the mineral jarosite. When the sulphates formed come into contact with moisture, sulphuric acid may develop: a corrosive and irritating acid.

For this reason, decaying pyrite is best disposed of carefully, as it can damage both health and nearby materials. The acid produced may leave burn marks on paper, wood, or other surfaces on which the specimen is placed. The best prevention is to keep pyrite specimens completely dry, although impregnating them with a protective coating such as paraffin wax can sometimes help.

Pyrite and marcasite

Not all pyrite behaves the same way. Pyrite from Peru and Spain tends to be quite stable, while material from chalk deposits in Germany and France is much more unstable. These unstable concretions are often referred to as marcasite, though tests revealed that they are often actually pyrite.

Having said that, true marcasite is chemically very similar to pyrite and has the same risk of decaying. The difference lies in their crystal structure; marcasite is a polymorph of pyrite, meaning it has the same chemical composition (FeS₂) but a different atomic arrangement. When these “marcasite” or pyrite nodules are broken open, they reveal a beautiful radiating, golden metallic pattern. Unfortunately, once exposed to air, they are extremely unstable and inevitably begin to decay…. it is not a question of if, but when they will start to deteriorate.

Pyrite in fossils

This type of decay also occurs in fossils, as pyrite commonly replaces parts of marine vertebrate bones and ammonites from certain fossil sites. For collectors and museums, preventing deterioration in such specimens is a constant challenge.

Various methods exist to delay or limit pyrite decay, such as impregnating the specimen with a consolidant, though these treatments can never fully guarantee stability, particularly if the reaction has already begun deep within the fossil.

Storage and conservation

The best way to preserve pyrite is to store it in a dry environment. Some people recommend keeping specimens in sealed containers or plastic bags, but this is only effective if the specimen is completely dry. If any residual moisture remains, it may later condense as temperatures fluctuate, creating a humid microclimate inside the container that accelerates decay. Fossils containing pyrite can be treated with a fixative to strengthen their surface, provided they are thoroughly dry. This can be a mixture of glue diluted with water or acetone.

Vanadinite is a popular mineral with beautiful reddish-brown crystals, but vanadium is a toxic element. Handling vanadinite in normal circumstances is not a problem, but care should be taken when crushing it, and with exposure to moisture and acids, etc.

Sulphur

Sulphur as a native element is not in itself very toxic or harmful. Even so, it is always wise to wash your hands after handling sulphur. Sulphur in powdered form can be dangerous if it is inhaled, and heating sulphur is also not a good idea (understatement, it is a very bad idea!). Sulphur vapour is dangerous to breathe in.

Gemstone water

Drinking gemstone water comes from the belief that water in which stones are placed absorbs the supposed properties of those stones. When you then drink this water, it is believed to have a positive effect on your health. I am often asked which stones are safe to put in drinking water. I tend to answer: “none at all”. Besides the risky stones I have discussed in this mini course, there are many more stones that are better not placed in drinking water. But even so-called ‘safe’ stones, such as quartz…. do you have any idea how minerals are mined?

After they are removed from the host rock (sometimes with the help of chemical agents), they have to be cleaned. They are often covered with deposits of, among other things, limonite, hematite and calcite. Buyers do not want this; they want clean and clear stones. So these impurities are chemically removed. When the stones are then polished, this is also done using chemical substances. While you may assume you are buying a clean stone, this is often what has already happened to it.Recently,

I examined a crystal-clear, cut rock crystal under the microscope. On the polished surfaces, residues of polishing compounds were clearly visible. With the naked eye, this was not visible at all. If you were to put such a stone in water, you would be drinking those residues.

Be careful with special bottles for gemstone water that have containers in which you can place the stones so that they are not in direct contact with the water. In some of these bottles, the stone compartment is glued in place, and the water can come into contact with this glue. There are also bottles in which this compartment is attached with iron wires. After being used a few times, the iron starts to rust. This leaches into the water and the compartment can come loose.

The much-praised shungite is also widely sold to be added to water. This is not a good idea. Shungite is by no means always pure carbon. Besides carbon, shungite-bearing rock often contains all kinds of other materials, including substances that are classified as heavy metals. Read more here about what shungite actually is and why it is better not to put it in your water.