There are a considerable number of minerals that belong to the feldspar group. For clarity, we’ll stick to the classification we learned in lesson 5a. Often, the varieties aren’t easy to distinguish visually without further analysis.

Plagioclase feldspar minerals

Albite: This is one of the most common feldspar minerals. It is triclinic and is usually classified by mineralogists as belonging to the plagioclase series, despite being an end-member of both groups. In petrology, it is classified as both plagioclase and alkali feldspar. It is usually white, hence the name, which is derived from the Latin albus. Sometimes it is referred to as high or low albite, referring to the temperature at which it formed. Variants of albite include peristerite, cleavelandite, and pericline.

Oligoclase: This is a plagioclase feldspar with a ratio sodium : calcium between 90:10 and 70:30, albite : anorthite. This means a higher sodium content and less calcium. Certain varieties of sunstone are oligoclase with hematite and ilmenite inclusions.

Andesine: This is the next plagioclase variety with a sodium : calcium ratio of 70:30 to 50:50. Coloured andesine is rare. Not long ago, a discovery of red andesine from Tibet caused quite a stir. Unfortunately, much of this andesine turned out to be yellow andesine from Mongolia. The Tibetan variety is very rare.

Labradorite: This is probably the best-known feldspar variety and, along with “moonstone,” the most highly prized. Labradorite falls within the plagioclase series in the 50:50 to 30:70 ratio and is therefore closer to anorthite than to albite. What is sometimes very striking about labradorite are the lamellae, which clearly demonstrate that it is a mixed crystal. If the solid solution becomes unstable due to the temperature being too low, demixing occurs, and the various components crystallize in separate lamellae. This gives labradorite its unique iridescence. Also called labradorescence or the Schiller effect. There are two important conditions for this effect to occur: there must be an anorthite content of 60-90%, and the solution must cool slowly to allow the atoms time to group together in this way. Therefore, not all labradorite exhibits this effect. Most labradorite commercially available comes from Madagascar. Spectrolite is a trade name for Finnish labradorite. A copper-containing red/green labradorite is found in Oregon and is called “Oregon sunstone” (unfortunately, there are many Chinese imitations of this stone on the market).

Bytownite: This is a type of plagioclase feldspar with 70-90% anorthite, making it a calcium-rich feldspar. Like labradorite, bytownite can have lamellae and display labradorescence. Sometimes, yellow bytownite is also called yellow labradorite.

The IMA (International Mineralogical Association, the body that determines new minerals and nomenclature) has not recognized labradorite and bytownite as separate minerals, but rather as varieties of anorthite.

Anorthite: This is the calcium-rich end member of the plagioclase series. It is a rare mineral on Earth, but common on the moon. It has also been found in a comet and in several meteorites. Anorthite-bearing rock is called anorthosite. The piece of anorthosite from the moon was called “Genesis Rock” because the astronaut who found it initially thought he had discovered the oldest piece of rock on the moon. Later, another piece turned out to be even older.

Alkali feldspar

Anorthoclase: You won’t encounter this mineral very often as a standalone mineral. It is, however, a component of many feldspar-bearing rocks. It is a triclinic mineral.

Sanidine, Microcline, Orthoclase: We will discuss these three different minerals together. They all share the same chemical composition. The difference lies in the temperature at which they formed. They are polymorphs, various manifestations of the same chemical composition. Sanidine forms at high temperatures and rapid cooling. If cooling occurs slowly, low-temperature microcline forms. Sanidine has a monoclinic crystal system, whereas microcline has a triclinic crystal system. Orthoclase forms during slow cooling when the initial cooling was too rapid. This mineral is pseudo-monoclinic. These crystals can grow to substantial sizes; the largest recorded crystal measured 10 meters in diameter. The Mars Rover has detected orthoclase in rocks on Mars. A large portion of the rocks brought back from the moon by the Apollo missions also contains orthoclase. Adular is a completely low-temperature variant of microcline and orthoclase.

Amazonite (non-official name) is a variety of microcline that derives its green colour from the presence of lead. It often exhibits the layered pattern common in feldspar, with alternating green and white bands, similar to labradorite, which results from exsolution or segregation. The lines, or lamellae, are also called perthite, where albite and alkali feldspar alternate. In amazonite, the green part is microcline, and the white part is albite. When the albite alternates with plagioclase, the term antiperthite is sometimes used.

Besides these two series, there are a few rare varieties that include other elements, such as this barium-containing celsian from Scotland.

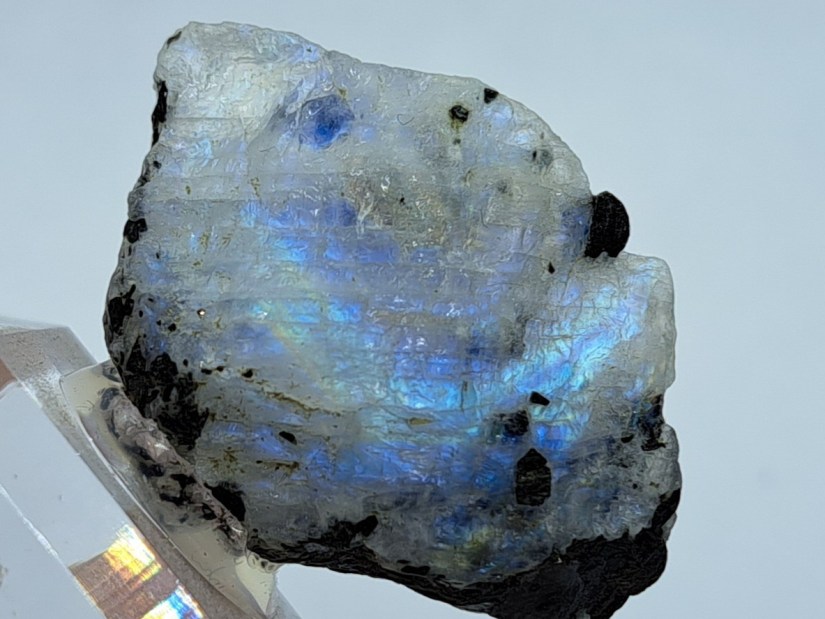

What is moonstone?

That question isn’t easy to answer, except that you can say “a feldspar.” Moonstone is a somewhat controversial term within the feldspar community, and the fact that nowadays every polishable feldspar with a satin sheen is sold as this or that moonstone is a common misnomer.

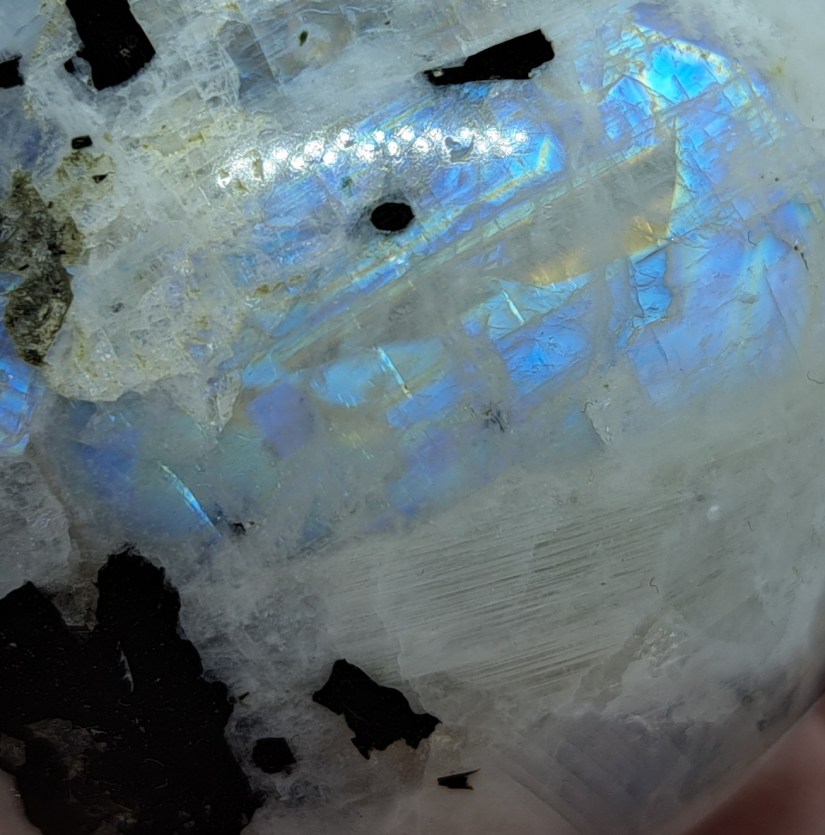

There isn’t just one type of moonstone; what we call moonstones are various kinds of feldspar. Moonstone isn’t an official mineral name either; it’s a term used for white or colourless feldspar exhibiting a beautiful Schiller effect or adularescence. “Common” gray moonstone is typically microcline, sometimes albite. Most of the confusion typically arises from the so-called “rainbow moonstone,” a feldspar characterized by its stunning iridescence.

This interaction of colours, similar to labradorite, results from the separation of different feldspars, leading to the formation of lamellae. Albite with the Schiller effect is also known as peristerite. The well-known Sri Lankan rainbow moonstone was believed to be a mixture of orthoclase and albite (Spencer 1930), and is therefore classified as an alkali feldspar.

Recent studies confirm that the Sri Lankan rainbow moonstone samples are indeed orthoclase. According to this research, the adularescence in this variety results from perthite, the lamellar growth of alternating types of feldspar, in this case, albite and orthoclase. This rainbow moonstone exhibits fewer of the typical parallel lamellae, instead featuring lens-shaped lamellae. Consequently, the moonstone has less brilliance than labradorite, but displays a deeper, more opalescent, and seemingly more transparent lustre. This rainbow moonstone is sometimes referred to as white labradorite. Still, this name is technically incorrect because labradorite belongs to the plagioclase feldspars, which are part of the other feldspar group. It also lacks the parallel lamellar arrangement found in labradorite. It is usually difficult to determine the exact origin of commercially available moonstone.

A recent analysis of several Indian specimens (by R. Egberink) reveals that some of the Indian ‘moonstone’ varieties are composed of orthoclase/albite. However, some specimens also exhibit characteristics of plagioclase, and the analysis indicates that the lamellae of these specimens are composed of albite/anorthite. Therefore, technically, these could be called white labradorite.

Recently, many new types of moonstone have appeared on the market, including black, pink, and green varieties. I’m not aware of any analyses of the black moonstone, so it’s hard to determine which type of feldspar it is. Pink peach moonstone from Madagascar is identified as microcline. The green variety is said to contain garnierite and originates from Madagascar. This green garnierite moonstone appears to have two forms: a colourless base of feldspar with a light green undertone, and pieces that show significant green colouration in the cracks. I submitted the latter for analysis. The test results indicated that the sample did not contain garnierite or any other nickel mineral, and traces of dye were found in the sample. This does not imply that all green ‘moonstone’ is dyed, but it certainly raises suspicion about the bright green ones with significant colouration in the cracks.

And what about sunstone?

Sunstone is an unofficial name for colourless feldspar (usually microcline or oligoclase) with inclusions of copper, ilmenite, hematite, and magnetite, among other minerals. Sunstone is found in Norway, Russia, the United States, Canada, Tanzania, India, and Australia. Sunstone with copper inclusions from Oregon is the state’s gemstone. This variety is highly prized as a cut stone in jewelry.

A sought-after and beloved variety is the so-called Rainbow Lattice Sunstone. It owes its name to a lattice pattern in which the inclusions are organized. The plate-shaped hematite inclusions reveal a beautiful rainbow colour palette with the right angle of light. Until recently, Australia was the only source of this Rainbow Lattice Sunstone. All sunstone from there comes from pegmatite near Harts Range in the Northern Territory. These were originally mica mines. According to descriptions, the rocks there are heavily weathered, and the RLS is hand-picked from this weathered material.

Recently, a sunstone with beautifully arranged lattice-like inclusions from Tanzania came onto the market. This Tanzanian Lattice Sunstone is not easy to distinguish visually from the Australian one, especially when they are not seen side by side. People who see a lot of this material notice differences in, among other things, the clarity of the feldspar (the Tanzanian is somewhat cloudier), the moonstone-like sheen (this is more pronounced in the Australian), and small details in the inclusions. Larger pieces of the Australian are also not often seen. Unfortunately, no analysis of the Tanzanian is available yet, so actual differences based on composition cannot yet be mentioned. The Tanzanian is usually slightly less expensive than the Australian. This has nothing to do with quality, but rather with the costs incurred in both countries to extract and process this material. This is the reason why sometimes ‘cheaper’ Tanzanian sunstone if sold as more expensive Australian.

Analysis of this Australian RLS shows that it consists of a combination of predominantly oligoclase lamellae with very thin albite layers and inclusions of magnetite and hematite. The alternating lamellae creates the characteristic iridescent light effect also found in moonstone, for example, and referred to by terms such as adularescence or the Schiller effect. The magnetite and especially the hematite inclusions create the rainbow confetti (aventurescence) and grid-like patterns in the stone. When examined with a magnifying glass, it is clearly visible that there are various inclusions. The magnetite is dark, grayish-black or brown, thin, elongated, blocky, or triangular. The hematite is lighter, silvery, red, or orange with tints that create the rainbow effect under the correct light. These are mainly thin ‘platelets’ or red flecks. Magnetite and hematite are both iron oxides. The magnetite most likely formed from iron released from the feldspar and not from external influences. The hematite was not a primary inclusion; it formed through oxidation of the magnetite. The inclusions follow the orientation of the feldspar lamellae and therefore lie predominantly in parallel planes/layers.

Graphic granite

Graphic granite is a type of rock that is an epitaxy of smoky quartz and feldspar. The term epitaxy is derived from the Greek ‘epi’, over or upon, and ‘taxis’, which means order. When two minerals grow together epitactically, this is not random, but it follows a certain order. This type of growth can only occur when both minerals have a reasonably similar crystal lattice, so one mineral can be the basis from which a second mineral grows. We know this type of growth from several minerals, like graphic granite, lattice quartz and hematite with rutile. In graphic granite, layers of feldspar and quartz follow each other. A feldspar layer grows from a pegmatitic solution. When the solution contains too high a percentage of silica, the growth of a layer of quartz begins. The feldspar base forms the seed surface for the quartz crystals that will all grow in the same direction due to the arrangement of the already present feldspar crystals. If the silica percentage drops, another layer of feldspar follows. Again there comes a turning point where the silica becomes dominant again and another layer of quartz is formed. This can continue until the solution has crystallized completely.