No… not the music genre. Metals in minerals that can be harmful for your body. Not all equally dangerous, not all dangerous in equal quantities. So let’s discuss the most important ones.

“Heavy metals” is a collective term for a number of elements, metals, with a high atomic mass. It is usually taken to mean the metals that lie between copper and lead or bismuth in the periodic table of the elements (strictly speaking, the first two we will discuss do not really belong in this category, but I would still like to include them). A mineral that contains heavy metals is not, by definition, toxic; this depends on several factors. Heavy metals to be particularly aware of include arsenic, cadmium, lead, thallium and chromium.

Metals are things that do not initially seem especially dangerous, largely because we are so used to having them all around us in everyday life, and because metallic elements are also essential to the human body. Iron, for example, enables our blood to transport oxygen. Without it, there would be no life. Vitamin B₁₂ is produced with the help of cobalt. Zinc is essential for our immune system and nervous system. But, as with everything, too much is harmful. If I were to put a glass of water in front of you and tell you that I had dissolved some copper in it, you would probably leave it untouched. Yet if someone gives you a glass of water and tells you it is crystal water made with chrysocolla, many people would not think twice, even though many minerals contain exactly these kinds of heavy metals.

Fortunately, most minerals cannot do much harm if they are used sensibly. In polished form, most can be worn as jewellery without concern, and they can safely be kept in a collection. What I would not recommend, however, is making crystal water or gemstone elixirs from them. Although they appear to be solid, hard stones, when placed in water they will always release small amounts of their components into that water. Consuming such water over a long period is not healthy. Why do you think there are now regulations governing metals in things like water pipes? There is already enough metal in our drinking water, sometimes even too much. There is no need to add a stone to it and increase those levels further.

We will not discuss every metal, as some are extremely unlikely to be encountered in minerals at all. For a few, however, I would like to linger a little longer, because there is a great deal to say about them.

Chromium – Cr 24

Chromium was first discovered as an element in the mineral crocoite. At the time, it was thought that the mineral consisted of lead with selenium and iron, and it was therefore given the name Siberian red lead. Only later did it become clear that, in addition to lead, it also contained a new element. Chromium later became popular as an ingredient in pigments.

Not all forms of chromium are equally dangerous. It has many useful applications in industry. For example, it is used in many alloys, helps to purify glass, and is used in the tanning of leather. Car enthusiasts will certainly be familiar with the process of chromium plating: coating metals with a thin layer of chromium (there are even songs about it), so that they shine beautifully and are more resistant to corrosion (rust). Chromium is also added to stainless steel for this reason.

Trivalent chromium is required by humans in very small amounts for metabolism. The dangerous form of chromium is Cr⁶⁺, or hexavalent chromium.

In addition to crocoite (wash your hands after handling, do not give it to children, and do not put it in your water), quite a few minerals contain small amounts of chromium. Fortunately, these are usually virtually harmless. Besides chromium, crocoite also contains lead, which means it is a mineral that should be handled with care.

Lopezite contains hexavalent chromium and is unfortunately still widely sold without any warning or proper information. You are unlikely to encounter natural lopezite, or potassium dichromate, on the market, but it does exist. The lopezite that is encountered is produced by people using naturally sourced potassium dichromate powder as a raw material. The bright red crystals that form look very attractive, but they are highly dangerous. The substance is classified as carcinogenic.

It dissolves at relatively low temperatures and with minimal humidity. Simply handling a specimen with warm, slightly sweaty hands already poses a risk. Sadly, such pieces are still regularly offered for sale on websites, at fairs, and in shops without any warning. Inhalation of the material is hazardous, as is contact with the skin and eyes.

This is a mineral that is best avoided altogether. Because of its bright red colour and shiny crystals, it is particularly attractive to children, but it is absolutely unsuitable for children’s hands, or even adult hands.

Cobalt – Co 27

For most people, cobalt is best known as a colour pigment, particularly for the deep blue tones it produces in glass and ceramics. However, among miners in earlier centuries, cobalt had a much darker reputation. This was largely because it was often found in association with toxic arsenic, something miners feared greatly. In fact, the name cobalt is derived from the German word Kobold, meaning goblin or evil spirit. Miners believed these mischievous creatures had hidden the worthless, poisonous ore in the earth to deceive them.

Cobalt is indeed toxic, though fortunately it is not commonly encountered in mineral collections. Some of the more well-known cobalt-bearing minerals include erythrite and skutterudite, both of which contain arsenic in addition to cobalt.

Most of the world’s cobalt today is not mined directly, but rather recovered as a by-product during the extraction of nickel and copper. That said, minerals such as erythrite, cobaltite, and skutterudite remain important cobalt ores and are still used in cobalt production.

Cobalt: usefulness, history and modern issues

Cobalt has been a valuable element since ancient times. The ancient Persians, Greeks, Romans and Egyptians knew it could be used to colour glass, and cobalt glass remains popular to this day. It gives glass an intense blue colour; a well‑known type is Bristol blue. Modern production uses potassium cobalt silicate, and the product is known as smalt.

Cobalt was also used as a pigment in porcelain by the Chinese, producing the familiar cobalt blue, historically derived from skutterudite. Cobalt oxide paints were likewise used to decorate Delftware. Paints containing cobalt are slightly toxic when made from smalt, the principal risk being the powdered form and the possibility of inhalation.

Today cobalt is indispensable in our modern society. It is one of the most important components of rechargeable batteries and is sometimes referred to as “blue gold” due to its significant value in the energy transition. Most cobalt originates from the Congo (about 74%), largely as a by‑product of copper mining. Roughly one fifth of these mines are so‑called “artisanal” operations, essentially large open pits where copper and cobalt are extracted without adequate equipment or safeguards. Mining conditions there are often appalling. In some sites thousands of extremely poor people, including whole families with children, work by hand to extract rocks that may contain hazardous elements.

Cobalt sulphate has also been used briefly as an additive in some beers to help maintain a stable head. This caused health problems among heavy drinkers.

Vitamin B12 (cobalamin) contains cobalt as part of its structure, so in tiny amounts cobalt is essential to human health. It plays roles in metabolism, the nervous system and the production of red blood cells. The cobalt in dietary vitamin B12 is not comparable to metallic or mineral cobalt: in the vitamin it is incorporated into a complex ring structure and tightly bound to other chemical groups. Cobalt poisoning can occur from, among other sources, exposure to cobalt‑containing dust (so take care when cutting or polishing cobalt‑bearing minerals) or from oral ingestion.

Cobalt has a synthetic radioactive isotope, cobalt‑60, which does not occur naturally. It is produced industrially by irradiating the stable isotope cobalt‑59 with neutrons. Cobalt‑60 has several industrial uses and is also used in cancer therapy. It can, in theory, be formed by the decay of iron‑60, but that is extremely rare in nature. The notion of a “cobalt bomb”, a nuclear weapon intended to generate long‑lasting fallout of cobalt‑60 to render areas radioactive, remains hypothetical and is a trope of books and films; there is no evidence that such a weapon actually exists. There have, however, been experiments involving cobalt in nuclear weapons research, and a few incidents have occurred in which waste containing radioactive cobalt was melted into scrap metal and later used in manufacturing; the resulting metal was found to be slightly radioactive.

Copper – Cu 29

Copper is a metal found in a remarkably wide range of minerals. Among the most well-known are the green-hued malachite and the deep blue azurite. Not all copper-bearing minerals are inherently dangerous. I’m mentioning it here because copper is an extremely common element in stones and crystals. However, under normal use, such as handling or wearing as jewellery, it is seldom genuinely hazardous.

The situation changes if someone were to regularly consume gemstone-infused water made with copper minerals, though one would hope no one is doing that. Acute copper poisoning is exceedingly rare. In medical terminology, it is sometimes referred to as copperiedus. It most often occurs in individuals who have a genetic disorder that prevents their bodies from properly processing copper.

For people without such a condition, it would take a very high intake over a prolonged period to become ill from copper exposure. Extended and excessive exposure can lead to liver and kidney damage. Healthy individuals are quite capable of processing reasonable amounts of copper, and the body has effective mechanisms for eliminating any excess. At present, there is some ongoing research into a possible connection between copper toxicity and Alzheimer’s disease, though no definitive conclusions have been reached.

Copper in water, however, is a different matter, particularly in aquatic environments. Elevated copper levels can harm marine life. Shellfish and fish are especially sensitive, and excessive copper can cause illness or even death in such species.

It is a misconception that malachite is inherently poisonous. That said, malachite powder is officially classified as a hazardous substance. The ancient Egyptians used it as a form of eye makeup (known as Udju), but such usage is certainly not recommended today, especially daily. To put things into perspective: simply holding a piece of malachite in your hand or wearing it as a pendant poses no danger at all.

Copper has been known to humankind since time immemorial. In antiquity, it was already being extracted and used for decorative objects as well as weapons. The oldest known copper artefacts date back to the Neolithic period. Copper was relatively easy to obtain and could be found in many regions, making it an accessible material for early societies.

The era in which copper was widely used is referred to as the Chalcolithic or Copper Age. One famous example from this period is the Ice Mummy Ötzi, who was found carrying a copper axe. When copper is combined with tin, it forms bronze—a much harder and more durable alloy. This marked the beginning of the Bronze Age, named after this important advancement.

Copper proved suitable for a wide range of applications and was relatively easy to work with, making it an essential material in the development of early human technologies.

Chalcanthite

Chalcanthite is a copper sulphate mineral that occurs naturally in the environment. It’s known for its striking, bright blue colour and is considered one of the more visually appealing copper minerals. However, the majority of chalcanthite found in shops or at mineral fairs is not natural at all, it is synthetic, produced in laboratories.

These vivid blue crystals often fade over time to a paler shade. With a bit of experience, it’s quite possible to learn how to distinguish between natural and synthetic chalcanthite, but one of the easiest clues is often the listed ‘locality’. If the specimen has large, well developed (not fibrous or small druzy-like) crystals like the single crystal on the photo above and is said to be from Poland, it is almost certainly lab-grown rather than naturally occurring.

That said, both natural and synthetic forms of chalcanthite pose health risks. It’s best not to handle them too often, and they should always be kept out of reach of children. Ironically, their bright blue colour tends to attract children, so caution is especially important. Chalcanthite can irritate the skin, eyes, and respiratory system.

Bright blue copper sulphate powder also sometimes appears in old chemistry kits or “grow your own crystal” sets. In powder form, the risks are even greater due to the potential for inhalation. In truth, these kits are not suitable for children, even though they are often marketed towards them.

Copper sulphate: uses and hazards

Copper sulphate is registered as a pesticide in many countries. It is highly toxic to aquatic life and is sometimes used to control certain bacteria in water. However, this practice can have unintended consequences, particularly for people who rely on that water for drinking. In fact, copper sulphate contamination is suspected to have played a role in a major outbreak of illness on Palm Island in the 1970s.

In addition to targeting bacteria, copper sulphate is effective against fungi, slugs, and even some plant species. If ingested in powdered form, copper sulphate can cause acute illness in humans. Symptoms typically include nausea, vomiting, and diarrhoea. Notably, both vomit and stool may appear blue due to the compound’s distinctive colour.

Copper sulphate is also occasionally added in minute quantities to wine, where it helps neutralise unpleasant sulphur-like odours that can develop during the fermentation process. When mixed with quicklime, it forms Bordeaux mixture, a well-known fungicide used in vineyards to combat mildew and fungal infections.

Arsenic – As 33

With arsenic, I would like to spend a little more time. It is an element that people tend to fear because it is so well known as a poison. It also has an incredibly fascinating history. That is why we will give it some extra attention here and spread the topic over several days. The best-known minerals containing arsenic are probably orpiment and realgar. Most people are also now aware that so-called bumblebee jasper contains arsenic in the form of realgar. But what exactly is arsenic, and how toxic is it really?

To ease concerns straight away: the risk of acute poisoning does not apply to the minerals just mentioned. Yes, they are toxic, but acute poisoning is virtually impossible in these cases (unless you start eating large quantities). I will explain later how the toxicity of different arsenic-bearing minerals works exactly.

Arsenic was most likely discovered as early as the 13th century by Albertus Magnus, but it was not until the 17th century that methods for isolating arsenic as an element were described. We distinguish between organic arsenic (which occurs in living organisms, including humans) and inorganic arsenic (found in ores and minerals). Today, arsenic is used in industry and, to a very limited extent, in medicine, for example in the treatment of certain forms of leukaemia and syphilis. Unfortunately, there are still countries that use arsenic as a pesticide and in wood treatment to protect against things like woodworm. Given the toxicity of arsenic, this is strongly discouraged and has been banned in many countries. Occasionally, it is also used in alloys.

Arsenic is not particularly rare and occurs almost everywhere in the soil. When higher concentrations are present, this can lead to excessive amounts of arsenic entering groundwater and, as a result, cause arsenic poisoning in humans through drinking water. This is a common problem, particularly in China, India and Bangladesh. It can also occur when crops grown on such soils absorb arsenic; consuming these crops then leads to arsenic intake. A well-known example is rice, but tobacco is also affected. The historical use of arsenic in pesticides has made this problem even worse.

Arsenic is extracted from minerals such as arsenopyrite, realgar and auripigment, but in much mining and metal extraction it occurs as a by-product. This, together with the use of other heavy metals in mining, often leads to heavily polluted areas around metal mines and contamination of water supplies. The release of arsenic-containing dust from these mines also poses a hazard. During the smelting of certain ores, arsenic is released as vapour. Some types of coal also contain higher levels of arsenic, which is released when the coal is burned.

Today, arsenic is regarded as a critical element, meaning that it is important for modern technology. It is needed, among other things, for telecommunications equipment, ammunition, LEDs, batteries, solar panels and space technology. Peru, China and Morocco are important suppliers of arsenic.

Arsenic history

Since classical antiquity (and perhaps even before that) it was known that arsenic was an ideal poison. It was virtually untraceable, it left no visible traces. Perfect for poisoning someone. And that happened countless times. We know that a number of Roman emperors (and their wives, mistresses, opponents, etc.) had a predilection for arsenic. The story goes that Nero got rid of his stepbrother Tiberius Claudius Caesar Britannicus with a bowl of soup in which he had arsenic added. Nero’s mother, Agrippina, had already gained experience with this poison (she had, among others, her husband, Emperor Claudius, Britannicus’ father, murdered), so his son did not get this from a stranger. Of course, the soup had first been given to a taster. He indicated that the soup was fine, but much too hot for his master. And that’s where it went wrong. Nero had the soup diluted with cold water containing dissolved arsenic sulphide. So, the soup went to Britannicus who dropped dead at the first bite. Or so the stories go… Of course, historians have worked on this. When you ingest arsenic, you don’t drop dead immediately, you will die a very painful and slow death. So somewhere in this story something is not entirely correct. Either another poison was used, or he took a little longer to die. Unfortunately, we can no longer ask.

Alchemists were fascinated by arsenic. Until the Middle Ages the only sources of arsenic were minerals, and then in particular auripigment and realgar. You don’tjust hide these in someone’s food or drink. They are said to have a rather strong taste in this form (I haven’t tested it) and are difficult to dissolve in water. An odourless and tasteless disguise doesn’t work when you have to rely purely on these stones. It only really became popular as a poison when it could be mass-produced and easily obtained in a form that was odourless and tasteless and for which there was no good test at the time to show that it had been used as a poison. The Arab alchemist Jabir ibn Hayyan succeeded in obtaining an arsenic acid by heating and distilling arsenic-containing minerals (realgar and auripigment). This form of arsenic (arsenic trioxide) is extremely poisonous, odourless and tasteless. It was seen as the perfect poison. The first people to use this were the Medicis and the Borgias in Italy. Those who got in their way could count on a portion of poison sooner or later. The English even came up with their own term for getting rid of people with poison, this was called ‘to be Italianated’. It was not until the so-called Marsh test was developed in the mid-19th century that arsenic poisoning could be identified in a body.

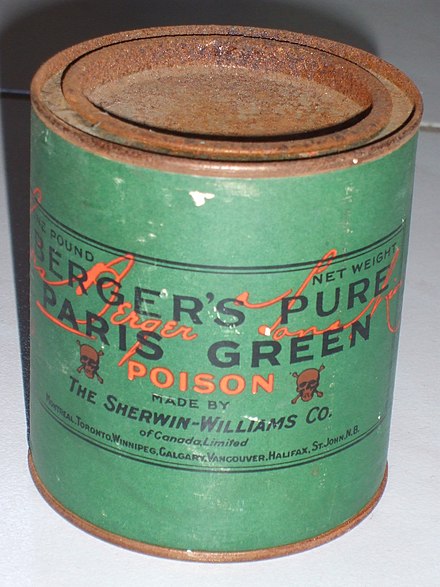

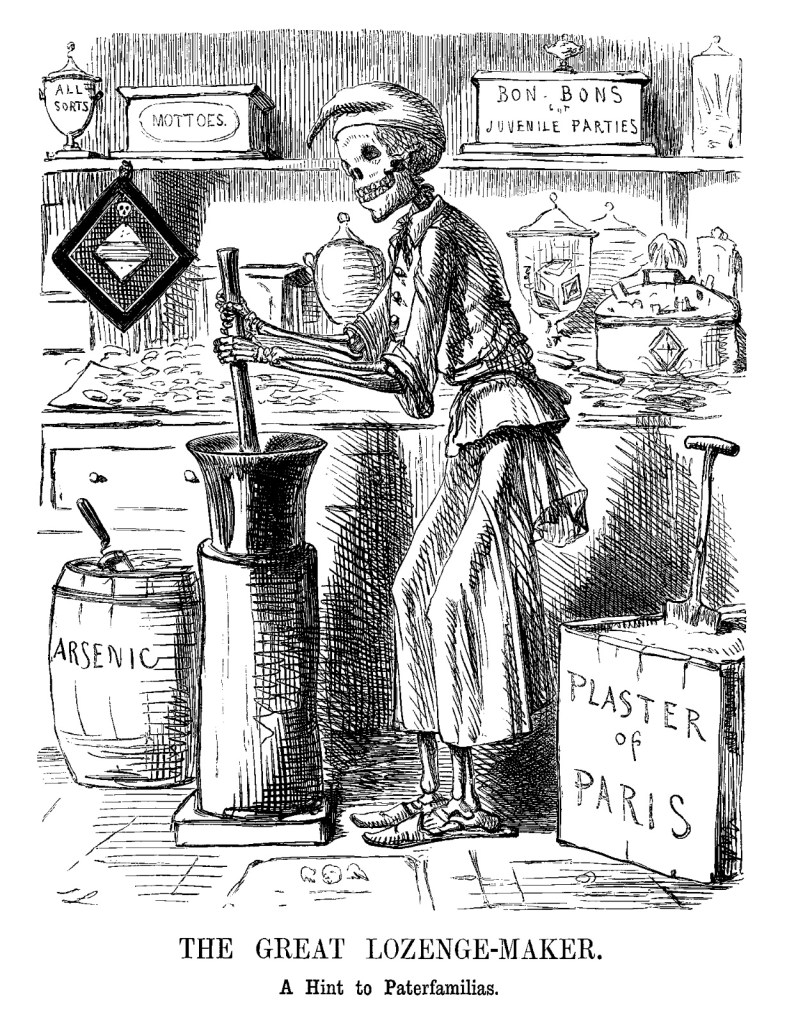

Paris green

Using arsenic deliberately as a poison is one thing. It is worse when it is added to objects everyone has in their homes and it enters your daily life without you even realizing it. And that is exactly what happened in the 18th and 19th centuries. It became very popular as a pesticide. It worked against every unwanted animal in the house. From insects to rats. At a time when rat plagues were the order of the day and houses were damp and swarming with vermin, it seemed a good solutionto use arsenic as a pesticide. In addition, it was discovered that mixed with copper it gave a beautiful green color that was very suitable as a dye. The first variant of this was called ‘Scheele’s green’, after the Swedish pharmacist Scheele who discovered it. The disadvantage of his paint was that it looked a bit yellowish. In the early 19th century this was improved and marketed under several names, of which we know the name ‘Paris green’ best (Veronese green and Schweinfurter green are other common names). It was used as a paint and as a pesticide. All the famous artists of that time were crazy about the beautiful green colour, including Vincent van Gogh, but also impressionists like Monet found it a beautiful colour to work with. It owes its name to the fact that the city of Paris used it lavishly to get rid of the rats in the sewers of the city. The use of this green paint and related pigments became so popular that it turned up everywhere. It was made into wallpaper, dyed fabric for clothing, book covers (these made the news not so long ago because they are now being removed from libraries), children’s toys, food colouring, furniture paint, you name it. And as if that wasn’t enough, there were also quacks everywhere who offered it in medicinal form in uncontrolled quantities.

Anyone who walked around in a house of the wealthy middle class in the 19th century could not avoid arsenic. It was everywhere. This had a huge impact on the health of the people at that time. And it was not that they did not know that it was poisonous. The use as a pesticide shows that. And even in that time it was the number 1 poison to kill people with. Especially in Regency and Victorian England it was everywhere. Even in Buckingham Palace the walls were covered with beautiful green wallpaper. When Queen Victoria realized what it really was and people had become ill, she had all the wallpaper removed. It took until the end of the 19th century for regulations to be introduced regarding the use of arsenic-containing paint. The use of Paris green as a pesticide continued for much longer. Until the Second World War it was used to combat mosquitoes, especially malaria mosquitoes. Entire areas were sprayed and it was poured into water to exterminate the creatures.

And then the big question… did Napoleon die from arsenic poisoning? For a long time, there was a persistent rumour that Napoleon Bonaparte was poisoned with arsenic in his exile on St Helena. Tests on his hair show that it did indeed contain a high concentration of arsenic, but not higher than before he was exiled and not higher than in the other people around him, such as his wife. The conclusion that is now drawn from this is that this arsenic came from his living environment, just like in every other house at that time.

Where it went terribly wrong…

Two examples from history where arsenic poisoning caused many victims can be found in England.

In 1858, 21 people died after eating sweets containing arsenic. An even greater number became ill. The maker of the sweets was rather stingy. Because sugar was expensive, he often replaced half of the sugar with plaster powder. Due to a careless mistake at the chemist where he bought his raw materials, he did not mix the sugar with plaster that fateful time, but with a bag of arsenic trioxide that looked like the plaster powder. The sweet maker became ill during the making but did not make the connection with the ingredients of the sweets. It was noticeable that the sweets looked a bit different than usual. But he sold his goods to the sweet shop in the neighbourhood nontheless. The sweetshop owner also noticed that the sweets were different. He even fell ill from a sweet he had tasted. But he still sold a large number of bags of sweets containing arsenic at his stall. Many people became ill, 21 died. It soon became clear what the cause was and all those involved had to answer for this in court.

In 1900, a striking number of people became ill in Manchester after drinking beer. Not immediately, it took quite a while before doctors noticed that people were not becoming ill from excessive alcohol consumption but were showing symptoms of chronic arsenic poisoning. Investigation led the authorities to the supplier of invert sugar. Because malt was expensive, a few breweries decided to replace their good quality malt with lower quality supplemented with sugar. Real sugar was also too expensive, so they used invert sugar obtained from the conversion of starch. At that time, sulphuric acid obtained from oxidized pyrite was used to produce this ‘sugar’. However, they did not know that pyrite sometimes contains arsenic in the crystal lattice as ‘pollution’. This arsenic ended up in the malt and therefore in the beer and caused some 6000 people to become ill, of whom it is estimated that 70 people died.

In Britain arsenic was produced for a while in the so-called arsenic labyrinth at the Botallack mine in Cornwall. It was built in 1906. Tin was mined in the mine. In order to extract the tin from the ore, it had to be heated to high temperatures. This process produced sulphur and arsenic vapour. This vapour was collected and passed through the labyrinth. As the vapour cooled, arsenic powder settled on the walls of the sealed labyrinth. Miners would go in and scrape this white powder, highly toxic arsenic trioxide, off the walls. This with very little protection. Just so you know, less than a gram of this stuff was enough to kill a grown man. The arsenic that was mined here was the raw material for the pesticide discussed earlier.

Medicine

Despite all its nasty properties, arsenic has been known as a medicine for centuries. There are stories about ‘arsenic eaters’ in Austria, people who slowly built up to eating arsenic daily and believed that it protected them (this story is questioned by many scientists). We know that people in the Middle Ages wore amulets containing auripigment and realgar as protection against the plague. For years, there was a famous tonic that was said to protect against all kinds of diseases, the Fowler Solution. Even Charles Darwin took medication with arsenic at a certain point in his life in the hope of finding a solution to his many health complaints.

Where prescribing such treatments up to about 100 years ago was a kind of Russian roulette, never knowing whether the illness or the medicine was making you sick, this has now changed. Modern medical science has shown, for example, that arsenic is very effective in treating certain forms of leukaemia. With the growing problem of antibiotic resistance, science also sees a potential future role for arsenic in medical treatments. In some Eastern medical traditions, arsenic is still used today. This is not always done responsibly (for example, in China you can apparently buy pills containing auripigment, realgar and arsenolite (arsenic trioxide) on street corners), but not all use in alternative medicine is of this kind. In more responsible traditions, scientific research forms the basis of the remedies.

In some Eastern medicine it is still used. This is not always done responsibly (for example, in China you can apparently buy pills with auripigment, realgar and arsenolite (arsenic trioxide) on every street corner), but not all use in alternative medicine is in this way. There too, scientific research increasingly is the basis of remedies.

Arsenic-beraing minerals

There are many minerals that contain arsenic. At present, Mindat lists 754 valid minerals that contain this element in greater or lesser amounts, far too many to list here. Fortunately, not all of them are dangerous. However, arsenic remains a toxic element, so whenever a mineral contains arsenic, the advice is to wash your hands after handling it and keep it away from children and pets. This may seem obvious, but it is worth repeating. Arsenic-bearing minerals are not suitable for placing in drinking water (so-called crystal water or elixer, and they should not be handled frequently or used for frequent physical contact.

The degree of toxicity depends on several factors, including:

- the type of arsenic compound

(arsenic trioxide in arsenolite is far more dangerous than arsenic sulphide in orpiment) - the solubility of the mineral

- the amount of arsenic present

In the chemical formula of a mineral, the presence of arsenic is indicated by As.

The best-known arsenic minerals are realgar and orpiment. These two minerals have been used for centuries as pigments in paint. It goes without saying that these paints were not healthy for the people who worked with them. The Egyptians ground orpiment to use as make-up, also not a particularly wise practice. The name orpiment comes from ‘auripigmentum‘, aurum (gold) and pigmentum, referring to its gold-like yellow colour.

These two minerals are chemically very closely related. They also form under almost the same conditions, hydrothermally. Both are arsenic sulphides, combinations of arsenic and sulphur. Sulphur compounds are generally quite stable, which means these minerals are not extremely toxic, despite their rather alarming components. They are very soft and break easily. However, they are not very soluble in water unless an acid is added. Orpiment is golden yellow to orange, and realgar is orange-red. When realgar turns yellow and becomes powdery, this is a sign that it is altering into pararealgar. Almost every realgar specimen exposed to light eventually undergoes this transformation. If you want to preserve a realgar specimen properly, it should be kept out of strong light.

If you have these two minerals in your collection, it is best to store them in a sealed container, out of reach of children and pets. If you have handled them, it is advisable to wash your hands thoroughly afterwards.

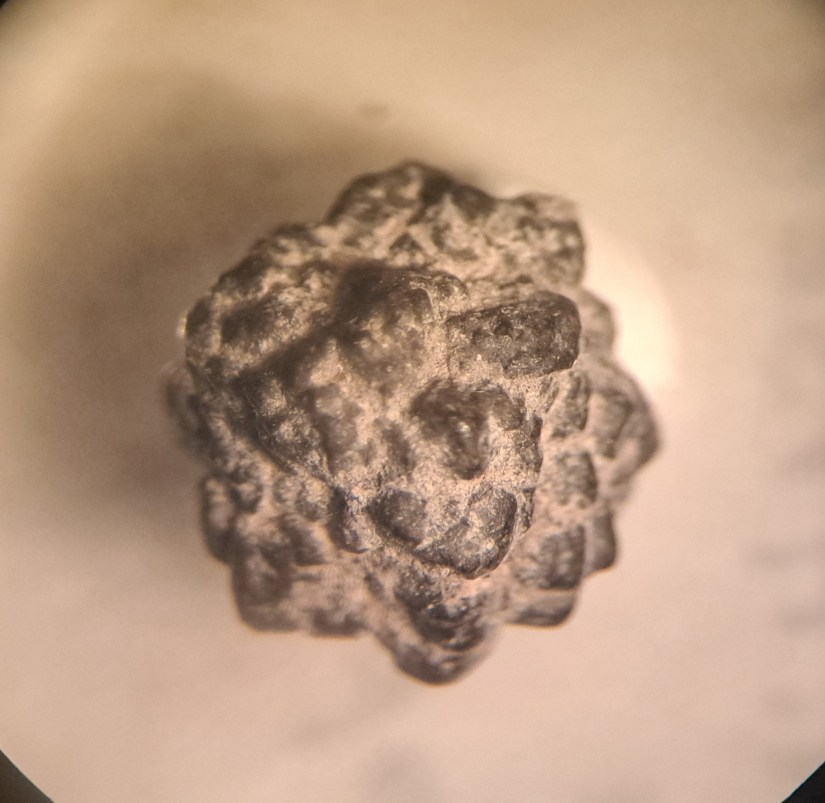

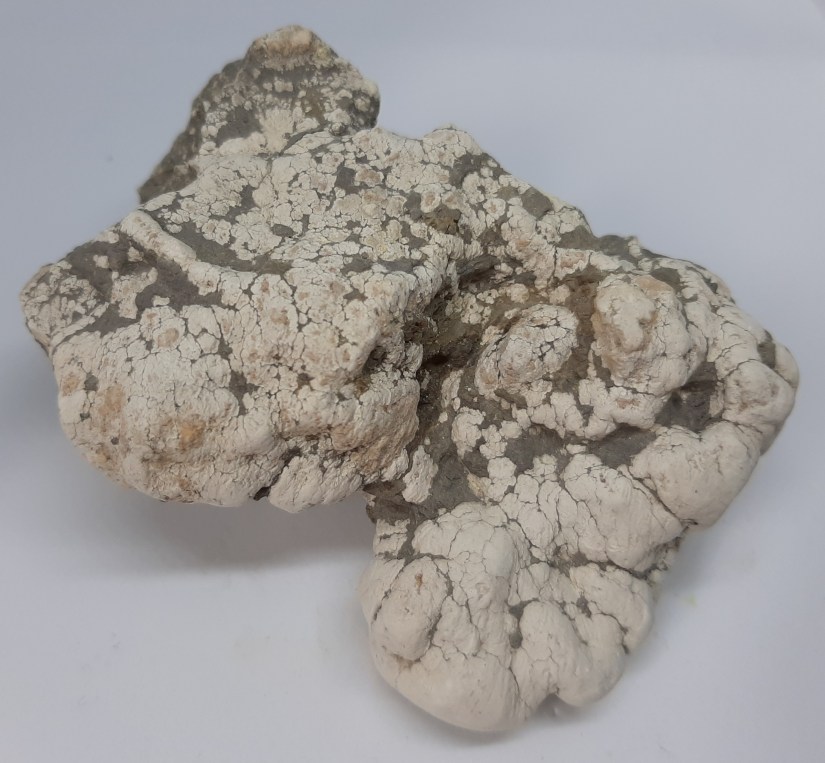

From Indonesia comes a white–yellow–grey rock composed of calcite, realgar and pyrite. It is sold under the name bumblebee jasper and sometimes also as eclipse stone.

The term “jasper” is incorrect in this case. The material is not a quartz-bearing rock, but a calcite. Calcite is considerably softer and more sensitive to acids. This makes bumblebee “jasper” a relatively soft and fragile stone. The presence of realgar makes the stone even softer. It is sometimes claimed that the yellow colour in this rock comes from sulphur, but this is incorrect. If you wish to use or wear this stone, it is therefore important to realise that it is an arsenic-bearing rock.

As with bumblebee “jasper”, the realgar within it is also subject to degradation, as shown in the photograph below.

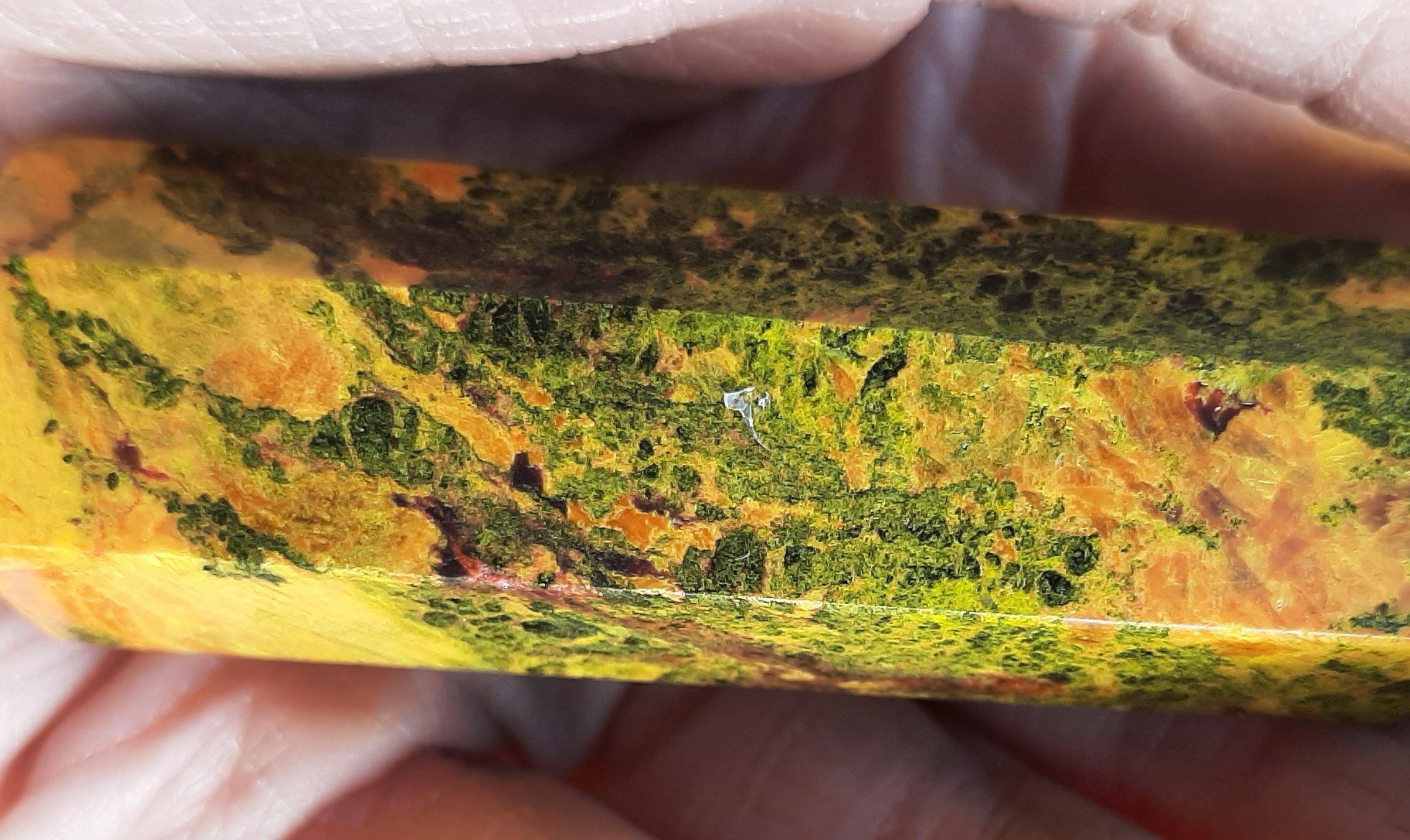

Recently, a new arsenic-bearing stone has appeared on the market. It is being sold under names such as “Chinese bumblebee jasper” or “Orpiment healing stone”. This material is a composite stone containing orpiment, (para)realgar, galena and epidote. It therefore contains both arsenic and lead, making it unhealthy.

This stone is mainly sold in the form of towers, spheres or other polished shapes. It is a very soft rock and crumbles easily.

Antimony – Sb 51

Antimony is the 51st element in the Periodic Table. The abbreviation Sb comes from the Latin name Stibium. We are most familiar with the metalloid antimony in the form of the mineral stibnite (also known as antimonite). Historically, this powdered mineral was popular both as a remedy to induce vomiting and as a black pigment in cosmetics. In ancient times, stibnite was finely ground into a black powder and mixed with fat to create a substance known as kohl, which was used as eye make-up. The modern-day kohl pencil is derived from this practice, but luckily doesn’t contain stibnite anymore. In addition to stibnite, galena was also commonly used in kohl, likewise not particularly healthy.

Stibnite was praised in various historical texts for its purported purifying properties and as a protective agent against the ‘evil eye’. In some cultures, even the eyes of young children were adorned with kohl for these reasons. The Romans used stibnite in the production of colourless glass. Antimony also attracted considerable interest from alchemists, many of whom documented processes for extracting and utilising the element.

Antimony is found in approximately 300 different minerals, with the most well-known being stibnite/antimonite, stibarsen, and boulangerite. Of these, stibnite is the primary ore from which antimony is obtained. The largest reserves are in China. Today, antimony is used in certain alloys, as a flame retardant, in the production of polyester textile, and in some types of batteries.

Although antimony and its compounds are toxic, they are generally regarded as less hazardous than substances such as arsenic, largely because the human body does not readily absorb them and tends to excrete most of the intake through urine. Most cases of poisoning have occurred because of improper medicinal use. To be safe, antimony-bearing minerals are best kept away from children and pets. Wash your hands after handling. Inhalation of antimony dust is dangerous. Don’t expose it to heat or strong acids. When handled in a normal way, these minerals are relatively safe to keep in your

Mercury – Hg 80

Chemistry

Mercury is a chemical element: a transition metal, represented in chemistry by the symbol Hg, derived from the Greek and Latin hydrargyros/hydrargyrum, meaning “watery” or “liquid silver”. It holds atomic number 80 in the periodic table. Uniquely among metals, mercury is liquid at room temperature (20°C), although a few other metals melt at only slightly higher temperatures. Mercury solidifies at -38.8°C.

Mercury is also known as “quicksilver”, referencing its silvery appearance. The term quick is rooted in the Old Saxon quik, meaning “alive” or “lively”.

Mercury is also the name of the planet. In antiquity, each known planet was associated with a metal. Due to its rapid orbit, the planet we now know as Mercury was linked to quicksilver and named after Hermes, the Greek god of free movement and travelers, and after the Roman god Mercurius, god of speed and communication. Over time, the name mercury became the accepted term for the element, while quicksilver gradually fell out of common use.

The principal source of mercury is the mineral cinnabar. Other mercury-bearing minerals used in mercury extraction include calomel, livingstonite, and corderoite. Cinnabar (HgS) appears in red, grey, or brown hues. It is relatively soft, 2 to 2.5 on the Mohs scale, and belongs to the trigonal crystal system. The precise origin of the name cinnabar is uncertain, though the term was already in use by Theophrastus (c. 371 – c. 287 BCE), who referred to it as κιννάβαρι (kinnàbari). The name likely has Eastern roots, perhaps from the Arabic zinjafr, meaning “dragon’s blood”.

To extract mercury from cinnabar, the ore is first crushed and then heated until the mercury vaporises. As it cools, the vapour condenses into silvery droplets, which were traditionally collected in glass bottles. Unfortunately, mercury in vapour form is highly toxic – making this work extremely hazardous.

Mercury in the Earth’s crust

Mercury is relatively rare on Earth, yet the International Mineralogical Association (IMA) has recognised nearly 90 mercury-containing minerals. Mercury forms compounds with elements such as oxygen, arsenic, tellurium, antimony, selenium, chlorine, iodine, bromine, and sulphur.

There are around 2,000 known localities where cinnabar has been found, the oldest deposits are over 3 billion years old. Many mercury minerals bear names unfamiliar to the average mineral collector; cinnabar remains by far the most well-known mercury mineral.

Cinnabar can form in several ways. Mercury tends to bond with organic material and is therefore often found alongside pyrite. In sedimentary deposits rich in organic matter, mercury more readily concentrates and crystallises. This explains why coal and black shale tend to have significantly higher mercury content than other rocks.

Cinnabar almost always requires heat and water to form, a process known as hydrothermal formation. This can occur at low temperatures, as seen in some American deposits where cinnabar formed alongside silica (quartz) and carbonates. However, more commonly, cinnabar forms under high temperatures, often in areas of volcanic activity that provide the necessary heat. To this day, both native mercury and cinnabar continue to form in high-temperature volcanic regions.

Supercontinents and mercury deposits

One remarkable finding from geological research is that many known mercury deposits correlate with the formation periods of supercontinents. A supercontinent forms when all Earth’s landmasses, which are constantly shifting, coalesce into a single, massive continent, unlike the present-day arrangement of separate continents. Earth has experienced several such supercontinents throughout its history.

The formation of these supercontinents typically involves significant volcanic activity and, consequently, the heat required for mercury mineral formation. The oldest documented cinnabar deposit was found in the so-called Greenstone Belt of South Africa, at Kaalrug Farm in the Barberton Belt, Mpumalanga Province, within the Kaapvaal Craton. This deposit is approximately 3 billion years old.

The most recent supercontinent was Pangaea, which began to break apart during the Cretaceous period. Around 40% of known mercury minerals first appeared during the formation of Pangaea. However, mineral formation did not cease after its breakup. The last 65 million years of Earth’s history, known as the Cenozoic, saw the emergence of 25% of all known mercury minerals.

This suggests that not all mercury mineralisation is linked solely to supercontinent formation. A plausible explanation for this high percentage is that younger rocks are better preserved. They have had less time to erode or be subducted back into the Earth’s mantle. Moreover, some mercury minerals are highly water-soluble and may have been leached or dissolved from older rock formations. Simply put, we know more about younger geological layers because they are more accessible and intact.

Well known cinnabar deposits

The largest known deposit of mercury in the form of cinnabar lies in Almadén, Spain. This single location accounts for roughly one-third of the world’s known mercury reserves. Geological research indicates that these deposits are at least 430 to 361 million years old. The name Almadén is derived from the Arabic المعدن (al-maʻdin), meaning ‘the metal’. Cinnabar has been mined here for over 2,000 years, beginning with the Romans and Visigoths. The region later came under Islamic rule, during which skilled alchemists developed methods to extract mercury from cinnabar. This mercury became a valuable commodity, traded widely across the Mediterranean.

In the 16th century, mercury became a sought-after metal in the New World, the recently discovered American continent, where it was used in the extraction of gold and silver from ores. The Spanish Emperor Charles V leased the highly profitable mines to the wealthy Fugger banking family, using the income to finance his election as Holy Roman Emperor in 1519. The extracted mercury was shipped from Seville to the Americas.

However, the history of Almadén has a darker side. Mining cinnabar was extremely hazardous, and workers often became ill and died from mercury poisoning after only a few years. For this reason, the mines were for long periods worked by forced labourers, prisoners, and slaves. During the 16th century, many convicted criminals, known as forzados, were put to work. These individuals were typically sentenced to a term as galley slaves, though working in the cinnabar mines was considered a lesser punishment. The forzados were relatively well treated, given sufficient food, clothing, and medical care, but even so, around 25% did not survive their sentence, usually due to mercury poisoning.

The most dangerous task was operating the furnaces, where cinnabar was heated to extract mercury vapour. Those prisoners who did not die from exposure often suffered long-term health effects. Over time, the forzados were gradually replaced by cheaper slaves, often captured in North Africa.

In the 17th century, the Fugger family’s right to exploit the mines expired, and control returned to the Spanish crown. From then on, those condemned to death sentences were employed in the mines. By the late 18th century, safer mining methods were introduced, and the use of forced labour and slavery was eventually abolished.

In the 19th century, ownership of the mines passed to the Rothschild family, who also controlled the cinnabar mines in what is now Slovenia (then part of the Austrian Habsburg Empire), thereby securing dominance over the European mercury trade. Substantial quantities of cinnabar continued to be mined until the 1940s, during which time prisoners of war from the Spanish Civil War were employed in the mines.

As the price of mercury declined, it became increasingly uneconomical to keep the mines in operation. By the early 21st century, the mines were permanently closed. Today, they are no longer active and, along with the mines in Idrija, Slovenia, have been designated as UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Furthermore, Almadén has been recognised as a site of Geological World Heritage. The mines are now open to the public and serve as an educational centre where visitors can learn about the history of cinnabar mining.

Presently, the extraction of cinnabar and the production of mercury is almost entirely dominated by China.

Idrija: Europe’s second largest cinnabar deposit

In Idrija, Slovenia, lies Europe’s second-largest cinnabar deposit. Mining activity in the region dates back to the Middle Ages. Over the centuries, hundreds of mine shafts and tunnels were excavated, many of which now pose a collapse risk to the town itself. As a result, extensive efforts are underway to seal and reinforce unstable mine workings to prevent subsidence.

There are no longer any active mines in the area. The only accessible mine today functions as a museum. Alongside Almadén, the Idrija mines form part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The cinnabar deposits here have been dated to approximately 245–235 million years ago.

Cinnabar in Italy

In Italy, cinnabar was mined in the region surrounding the extinct volcano Monte Amiata, located in Tuscany. These deposits are geologically young, having formed due to volcanic activity in the late Pleistocene. Between 1870 and 1980, large quantities of cinnabar were extracted, bringing significant economic prosperity to the region, but also loss of life due to the dangers of mercury exposure.

The most important mine in the region was that of Abbadia San Salvatore. Today, this mine also operates as a museum, preserving the memory and legacy of mercury mining in Italy.

Cinnabar in the New World and beyond

Following the discovery of South America, significant deposits of cinnabar were found in Huancavelica, Peru, in the mid-16th century. These deposits, dating back to the Miocene and Pliocene epochs, were considered valuable enough to merit full-scale extraction. This discovery reduced the need to transport mercury from Spain, as it could now be obtained locally. However, the Spanish Crown swiftly claimed ownership of the Peruvian mines, aiming to retain control over the mercury and cinnabar trade on both sides of the Atlantic. The largest of these mines was named Santa Barbara.

As in Spain, the mining of cinnabar in Peru was hazardous and often fatal, not only due to mercury poisoning but also as a result of numerous accidents, including the frequent collapse of mine shafts. Mercury was essential for the extraction of gold and silver from ores, making it an indispensable resource in the colonial economy.

To meet demand, the Spanish made use of forced labour systems. The Indigenous population of the Andes had long practised the ‘mita’, a form of communal labour. The Europeans co-opted this system, compelling Indigenous men to work in the perilous mines for one year, for meagre pay and basic provisions. This system persisted until it was officially abolished in 1812.

For a long time, Peru ranked as the fourth-largest producer of cinnabar in the world, following Spain, Slovenia, and Italy. The modern city of Huancavelica owes its very existence to the mining industry. However, in 1806, the Santa Barbara mine collapsed, effectively ending large-scale cinnabar production in the region. Attempts in the 20th century to revive mining operations proved unprofitable due to the declining global price of mercury.

Cinnabar in the United States

In the 19th century, substantial cinnabar deposits were discovered in California. The site of these new mines was named New Almaden, after the original Spanish location. Interestingly, the presence of cinnabar in the area had long been known to Indigenous communities, who used it as a red pigment.

Nearby, another deposit was named New Idria, after Idrija in Slovenia. These cinnabar deposits are geologically young, having formed after the Miocene epoch, less than 5.3 million years ago.

Unfortunately, many of these historic cinnabar mining sites are now severely contaminated, and the risk of mercury poisoning still affects local populations. In the United States, Italy, and Spain, considerable efforts have been made to decontaminate former mining areas, with notable success in many cases.

Historical use and cultural significance

The red pigment vermilion is derived from finely ground cinnabar. Owing to the rarity of cinnabar, vermilion was once an extremely expensive colourant. Long before the Common Era, it was used in China, Egypt, and Assyria. In India, vermilion was known as hinglu and held sacred significance, used in religious paintings known as pichhwai. The production process was ceremonial and could take several days to complete.

Archaeological evidence suggests that prehistoric peoples in Spain were using cinnabar as a pigment long before written history. Human remains from Neolithic and Bronze Age sites show traces of ground cinnabar on bones and burial items. Similar findings have been made in Israel, China, Anatolia, the Americas, and Syria. In Iron Age Spain, gold jewellery has been discovered containing cinnabar, likely used as an ornamental stone. Red, in Neolithic Spain, symbolised death. In megalithic tombs, red ochre was found on the walls and cinnabar on the bodies. Bone analysis reveals that at least some individuals had died from mercury poisoning linked to cinnabar exposure.

In Çatalhöyük, a Neolithic site in Turkey, the walls of ancient homes were painted with cinnabar pigments. In Serbia, excavations at Pločnik have revealed cinnabar traces on pottery and figurines, again pointing to its cultural significance in areas where the mineral naturally occurs.

Alchemy and immortality: Mercury’s mythic role

The ancient Chinese believed that mercury could grant immortality; a belief that tragically proved fatal for many. One of the most renowned fangshi (alchemists), Li Shao Jun (Li Shaojun), worked at the court of Emperor Wu in the 2nd–1st century BCE. Li was famed for his knowledge of mercury and cinnabar, believing they could be transmuted into gold through offerings to the spirit of fire. He convinced the emperor that gold created by this process could prolong life, and that using golden and cinnabar-infused utensils would aid his journey to the mythical island of Penglai, home of the immortals.

Similarly, Emperor Qin Shi Huangdi, the first emperor of a unified China, was buried in a vast necropolis. Ancient texts describe rivers of mercury flowing through the tomb to mimic the landscape of China. Modern readings have detected elevated mercury levels near the burial site, though the main tomb remains unexcavated. The Chinese government has prohibited further excavation due to the dangers posed by both toxic mercury and ancient traps rumoured to protect the emperor’s eternal rest.

In Hindu tantra, mercury (rasa, parada) and sulphur are regarded as cosmic elements. Mercury is seen as the sacred seed of Shiva. Texts like the Rasarvana, a dialogue between Shiva and Parvati, describe mercury as the origin of life, essential for both body and spirit. In this tradition, mercury is medicinal when correctly prepared, but poisonous when mishandled. The powerful compound nava-pashana, made from mercury and other toxic materials, was believed to confer eternal youth and was used in amulets, beads, and even in the casting of sacred statues.

Classical and early modern use of cinnabar

The Romans, Greeks, and Egyptians all used ground cinnabar in cosmetics, particularly as rouge. The Greek philosopher Theophrastus (4th century BCE) documented the use of cinnabar and how it could be ground in a copper mortar and mixed with vinegar to extract mercury, the earliest known written description of such a process. However, cinnabar residues have been found on Greek sculptures dating as far back as 2500 BCE.

The Romans regarded cinnabar as sacred. According to Pliny the Elder, they mined it extensively in Spain to produce vermilion, which was exported via Carthage across the empire. In Villa Boscoreale near Pompeii, extraordinary wall paintings have been discovered, rich in vermilion pigment.

Alchemy in the Islamic World and Medieval Europe

The 9th-century Persian alchemist Abū Mūsā Jābir ibn Ḥayyān, also known as Geber, was instrumental in the development of alchemical theory. He believed that all metals were composed of mercury and sulphur in varying purities. Gold, he claimed, was a union of the purest mercury and sulphur. This idea likely drew upon earlier texts such as the Sirr al-khalīqa (The Secret of Creation), an Arabic adaptation attributed (likely falsely) to Apollonius of Tyana. This text includes the famed Emerald Tablet, a short but foundational work in esoteric and alchemical traditions.

The Emerald Tablet introduced ideas such as the Philosopher’s Stone, the alchemical marriage of Sun (gold) and Moon (silver), and the axiom “as above, so below”. The author is traditionally identified as Hermes Trismegistus, a mythic figure associated with the Greek god Hermes (the Roman Mercury), further tying alchemy to the element mercury.

Geber’s writings heavily influenced medieval European alchemists, many of whom believed cinnabar and mercury held the key to creating gold and the elusive Philosopher’s Stone. Mercury’s unique properties led some to consider it the prima materia: the first substance from which all matter is derived.

Toxic beauty and industrial hazards

Mercury fountains were once popular in Islamic-Spanish palaces. The most famous stood in the 10th-century caliph’s palace in Córdoba, where the throne room shimmered with liquid mercury, reflecting sunlight across gold, marble, and gemstones.

A more modern example is the mercury fountain created by Alexander Calder for the 1937 Paris World Exhibition, commissioned by the Spanish Republican government as a protest against Franco’s occupation of Almadén. Displayed in the same pavilion as Picasso’s Guernica, the fountain symbolised the tragedy of war. Today, it can be viewed at the Fundació Joan Miró in Barcelona, safely enclosed behind glass.

In the felt industry, mercuric nitrate was commonly used to separate fur from hides during the felting process. This substance played a crucial role in the manufacture of felt hats. Unfortunately, hat makers often became ill from prolonged mercury exposure. This is the origin of the English expression “Mad as a hatter.” Symptoms of long-term mercury exposure included tremors, confusion, shyness, delirium, emotional instability, and loss of muscle control. Individuals suffering from these symptoms were often perceived as ‘mad’.

During the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries, cinnabar was still used in cosmetics. In France, it became fashionable for women to bleach their faces using creams and powders containing lead and mercury. Red highlights were created with cinnabar-based powders and ointments. In Italy, beauty ideals once favoured large pupils. Eye drops made from mercury-based solutions were used to achieve this effect, though inevitably, they caused eye damage over time.

Queen Elizabeth I of England followed the aristocratic trend of maintaining a pale complexion, applying lead-based products to whiten her skin. Her lips were coloured using mercury-based lipstick, and she removed her make-up using mercury-containing cleansers. One might assume we are wiser today, but sadly, this is not always the case. Skin-lightening products containing significant amounts of mercury are still sold, particularly in Asia, despite well-known health risks.

In more recent centuries, mercury was used in metal dental fillings, electrical switches, batteries, pesticides, thermometers, barometers, sphygmomanometers (blood pressure devices), and in gold extraction processes. Today, due to its toxicity, mercury is rarely used in household items or consumer products, although it still has various applications in industry and chemistry.

Environmental impact of mercury

It is worth reflecting on the environmental consequences of centuries of human activity involving mercury. Enormous amounts of cinnabar have been extracted, and mercury has been widely used in industrial processes. Additionally, vast quantities of coal containing mercury have been burned, releasing the metal into the atmosphere.

It is estimated that human activity has significantly increased the amount of mercury in the atmosphere. Once airborne mercury settles, it can be transformed by anaerobic organisms in aquatic environments into methylmercury, an extremely toxic form of mercury.

In the oceans, methylmercury accumulates in the bodies of fish, particularly predatory species. When humans consume such fish, they can be exposed to harmful levels of mercury. Because of this, safe consumption limits have been established for certain fish species, and pregnant women are advised to avoid eating large predatory fish altogether due to the risks posed by mercury contamination.

Cinnabar and mercury as medicine

Throughout history, cinnabar and mercury have been used for a wide range of medicinal purposes. They were popular treatments for parasites, syphilis, melancholy, itching and skin irritations, poisoning, fluid retention, and inflammation.

Mercury was widely used as a remedy for syphilis and other sexually transmitted diseases. It was administered in various forms: as ointments, oils, added to steam baths, and even as vaginal douches. Unsurprisingly, the side effects were often severe, and many patients died of mercury poisoning because of these treatments.

As recently as the 1940s, mercury (in the form of calomel, or mercurous chloride) was a component of powders given to babies to help with the pain of teething.

In India and China, cinnabar and mercury remain known ingredients in certain traditional medicines. For example, Zhu-Sha-An-Shen-Wan (Zhusha Anshen Wan) is a tablet-form medicine that is still available over the counter in China as a calming remedy for depression, panic, and insomnia. A significant ingredient in this medicine is cinnabar. Studies suggest that the toxicity of cinnabar in this formulation may be relatively low, possibly due to the presence of other substances that counteract its harmful effects, or due to the chemical form in which it is included. Nevertheless, the concentration of cinnabar in this medicine is thousands of times higher than what is legally permitted in Europe.

Health risks

Mercury is highly toxic. The greatest danger does not come from touching it, but from inhaling mercury vapour. These vapours are released from liquid mercury even at room temperature.

Cinnabar is a mineral made of mercury combined with sulphur, which makes it less easily absorbed by the body. Complete, intact crystals pose little risk when handled carefully. However, powdered cinnabar or more massive brittle pieces can be more dangerous, especially if they contain tiny droplets of native (pure) mercury. These are significantly more hazardous.

Never grind, crush, or heat cinnabar, and avoid inhaling any dust. If you’ve handled a piece of cinnabar, always wash your hands thoroughly afterwards.

Liquid mercury is far more dangerous. Even a broken thermometer or barometer can release enough mercury vapour to cause serious health issues, even if you think you’ve cleaned it up completely.

The production and sale of new mercury thermometers and barometers has been banned in most countries. However, older items can still be found in second-hand shops, antique stores, and flea markets. If such an item breaks, it is important to leave the room immediately and start ventilating right away. Do not walk over the mercury droplets, and never use a vacuum cleaner to clean them up.

Thallium – Tl 81

Thallium is an extremely toxic element. Fortunately, it is not very common in minerals. Well-known thallium-containing minerals include lorándite, hutchinsonite, and crookesite. These minerals must be handled with great care and stored securely. Thallium, along with arsenic, ranks among the most poisonous substances that can be found in minerals.

For a time, thallium was widely used as rat poison and insecticide. However, due to accidents and its use as a poison against humans, its use in these products is now banned. Thallium dissolves readily in water and is easily absorbed through the skin, so handling minerals containing thallium with bare hands is strongly discouraged.

Using thallium as a medicine is unwise, though it was done historically. For example, thallium was believed to help with certain symptoms of tuberculosis and ringworm. In the case of ringworm, patients, often children, were given thallium because it causes hair loss, making it easier to treat the disease on the scalp.

The only known antidote for thallium poisoning in the body is the administration of ‘Prussian Blue,’ also known as the blue pigment used in paint.

There have been numerous murder cases involving thallium, and it is a popular poison in literature. Agatha Christie, for instance, used thallium as the weapon of choice for some of her fictional villains. Even Saddam Hussein reportedly used thallium to eliminate his opponents by poisoning them.

Thallium still has some industrial and medical applications. It is mainly obtained as a by-product during the extraction of copper, lead, zinc, and other heavy metals. Manganese nodules found on the ocean floor sometimes contain traces of thallium. Be cautious with cosmetics as well, thallium has recently been detected in some mascaras.

Lead – Pb 82

Lead is another heavy metal that requires a degree of caution. It is not as dangerous as, for example, arsenic, but long-term exposure to lead is very harmful. Lead occurs in minerals such as galena (lead glance), cerussite and anglesite. Washing your hands after handling them is sufficient. It may be stating the obvious, but you should not make crystal water from these minerals.

A recent German study showed that amazonite also releases excessive amounts of lead when placed in a mildly acidic solution. According to the researchers, this implies that the same could happen if the stone is left in drinking water for a longer period of time. “Mildly acidic” here means water that is slightly sour, which is enough to leach lead from the stone.

Not all heavy metals are included in this list. On the one hand, this is because some are very rare, and the likelihood of encountering them in a mineral is extremely small. On the other hand, some are harmless in the form in which they occur in minerals. For example, barium is a highly toxic element, but in barite it is completely safe. Cadmium is a toxic element, but the chance of having a mineral in your collection that contains it is very small (sphalerite can be a source of cadmium because it occurs as a trace contaminant, but it is harmless under normal handling). Manganese is a heavy metal, but its toxicity is relatively low, especially in solid form, such as in minerals. In powdered form, however, it can be hazardous.