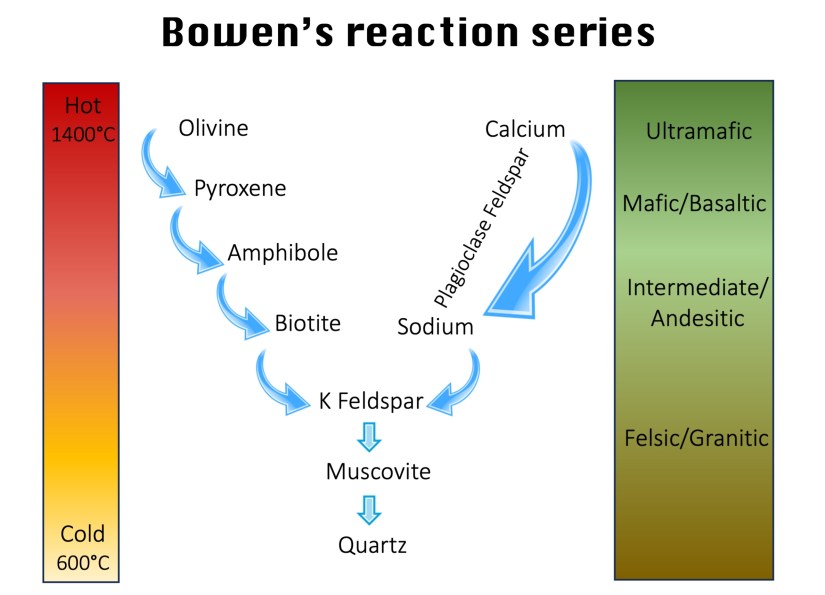

When discussing igneous rocks, we can’t ignore a well-known geological theory: Bowen’s reaction series. This is the theoretical order in which minerals solidify from magma. Imagine scooping a large pot of boiling magma from a magma chamber and placing it on a stovetop. As long as the fire burns, the magma stays hot. But if we turn off the heat, it cools very slowly. During this cooling process, the magma solidifies and turns into rock. Rock is a combination of different minerals. The order in which these minerals crystallize depends on the temperature.

Imagine the letter Y. There’s one trunk and two arms. We start at the top with the left and right arms. This represents the hottest magma, the highest temperature at which a mineral solidifies in the Earth’s crust. The left arm is a series of successively different types of minerals that solidify alternately as the temperature decreases. This arm is the so-called “discontinuous series,” because a new mineral is constantly being formed. The right arm is the “continuous series” and consists of one and the same mineral, plagioclase feldspar, with smaller variations within it. This is the so-called feldspar solid solution series (more on this in lesson 5, the lesson on feldspar). Where the arms meet in the trunk, we find the other feldspar series, the alkali feldspars. It also contains some micas and, at the very bottom, quartz.

Let’s return to our pot of magma simmering on the stove. This magma is ultramafic, meaning it’s rich in magnesium and iron, but low in silica. Now, we turn off the heat and observe how it cools and crystallizes. We’ll focus on the left branch of Bowen’s Reaction Series, the discontinuous series. As the temperature drops to about 1400 to 1200°C, the first mineral group to crystallize is olivine. This pulls magnesium and iron out of the melt, slightly increasing the relative silica content in the remaining liquid and making it a little less mafic.

As cooling continues, pyroxenes begin to form, followed by amphiboles, and then biotite (black mica). This sequence marks the progression down the discontinuous series, ending where it joins the stem of the “Y”.

At the top of the stem, anorthite (the calcium-rich endmember alkali feldspar) crystallizes. Further down, we see the formation of other alkali feldspars, muscovite mica and finally quartz. This is typically the last mineral to crystallize. At around 600°C the process is complete, and our pan holds a solid, layered rock.

If instead we had started with magma of low iron content, the crystallization would follow a continuous series, forming a range of plagioclase feldspars. The first to crystallize, at higher temperatures, are calcium-rich plagioclase. As the melt cools, the composition gradually shifts toward sodium-rich plagioclase, which crystallizes last. The result is a smooth transition from calcium-dominant minerals at the bottom to sodium-dominant ones at the top.

Now that we understand this, we can see why certain minerals tend to occur together. This process also helps geologists determine the temperatures at which different rocks form. However, there’s a big BUT… I called it a theory earlier, and I did so on purpose. While the process is theoretically solid, we rarely find rocks that are perfectly layered in the exact order Bowen described. Why is that? There are a few key reasons, though listing them all would take too long. Let’s focus on some of the most important ones.

The pot we used was all wrong. Instead of a simple soup pot, we should have used a pressure cooker! In other words, besides temperature, pressure plays a crucial role in determining the result. The rate at which magma cools also matters. Sometimes it cools slowly, allowing some crystals to melt back into the liquid, and other times it cools too quickly, disrupting the crystallization process. On top of that, foreign substances like water or other elements can mix into the magma, influencing which minerals form and sometimes throwing off the entire sequence. There are even types of magma where Bowen’s series doesn’t apply at all. Or volcanic eruptions, for example, change the temperature and composition of the magma.

So, while Bowen’s reaction series is a helpful theoretical model, it’s not a perfect blueprint. It’s a good tool for understanding how rocks form and why certain minerals are often found together, but it’s not always a one-size-fits-all guide.

Another thing Bowen’s series taught us is that it works the same the other way around. When you would melt a rock you can follow the opposite path, so bottom up. This also means that the minerals that form first, are the least stable ones under ‘normal’ Earth’s surface conditions. Minerals ‘feel’ most happy closest to the circumstances under which they crystallized. The ‘hottest’ minerals are more sensitive to westhering and decay than quartz.