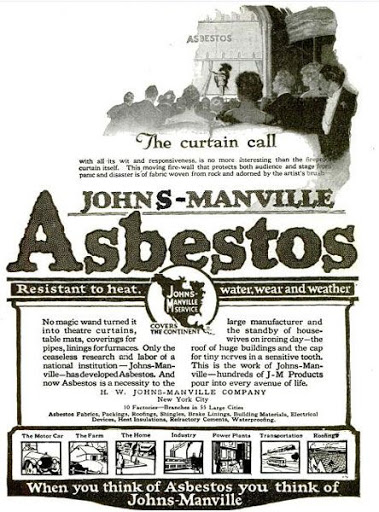

Asbestos is something most people sensibly prefer to avoid, and with good reason. Once widely used in a range of household products and building materials, it is now well established that inhaling asbestos fibres can cause cancer.

Despite its dangers, asbestos possesses several remarkable properties. It is strong, fire-resistant, and can be teased into fibres that can be spun and woven much like wool. These qualities led to its use in countless applications. Even in ancient times, people appear to have recognised its resistance to fire. Over the centuries, asbestos has featured in carpets, candles, oil lamps, cement, fireproof fabrics and materials, various types of insulation, imitation marble, cigarette filters, artificial snow, bakelite, the felt underlay beneath linoleum floors, and, of course, the familiar corrugated sheets.

Source Wikimedia Commons

Asbestos is a naturally occurring material comprising a group of minerals. These minerals fall into two categories: spiral-shaped fibres, known as the serpentine group, and straight fibres, known as the amphiboles. Amphibole minerals form a large family, and not all of them are hazardous or classified as asbestos.

The risk posed by asbestos is not determined solely by fibre shape, as was once believed when only straight fibres were considered dangerous. Instead, it is now understood that certain length-to-diameter ratios play a key role in its harmful effects. Some sources even describe asbestos not simply as a carcinogen, but as a substance that promotes the development of cancer.

A defining feature of asbestos minerals is their highly fibrous structure. However, the classification is not as simple as treating all fibrous minerals as asbestos; the mineralogical criteria are more complex than that.

One of the most hazardous forms of asbestos is crocidolite, commonly known as blue asbestos. For many years, it was thought to be the deadliest variety, responsible for the most severe illnesses. Today, however, several additional types are recognised as dangerous. Even white asbestos, or chrysotile, is now regarded as a cause of various diseases. There is still some uncertainty about which forms are the most harmful, so, as a precaution, multiple varieties are classified as hazardous minerals. The website mindat.org provides information on all asbestos-containing minerals and their associated health risks.

Other asbestos minerals include amosite, anthophyllite, byssolite, tremolite, and actinolite. The latter is still relatively common on the market. There is no need for alarm, as large deposits of actinolite occur naturally in countries such as Norway and Scotland. Crucially, only the fibrous form of actinolite is truly dangerous; the variety that forms large green crystals poses virtually no risk. Riebeckite is another hazardous fibrous amphibole mineral.

There are also minerals that are not formally classified as dangerous asbestos but are believed to cause similar health problems when inhaled in their fibrous form. These include erionite, fluoro-edenite, winchite, richterite, antigorite, nemalite, palygorskite, and sepiolite.

Asbestos becomes hazardous when inhaled or ingested, as the body cannot break down the fibres. Occasional exposure is unlikely to be fatal, but prolonged or repeated exposure can be life-threatening over time. Today, the use of asbestos is heavily restricted, although regulations differ widely from country to country. For instance, the United States still imports several tonnes of asbestos each year. There are also periodic reports highlighting asbestos contamination in talcum powder, including products used for cosmetics and baby care.

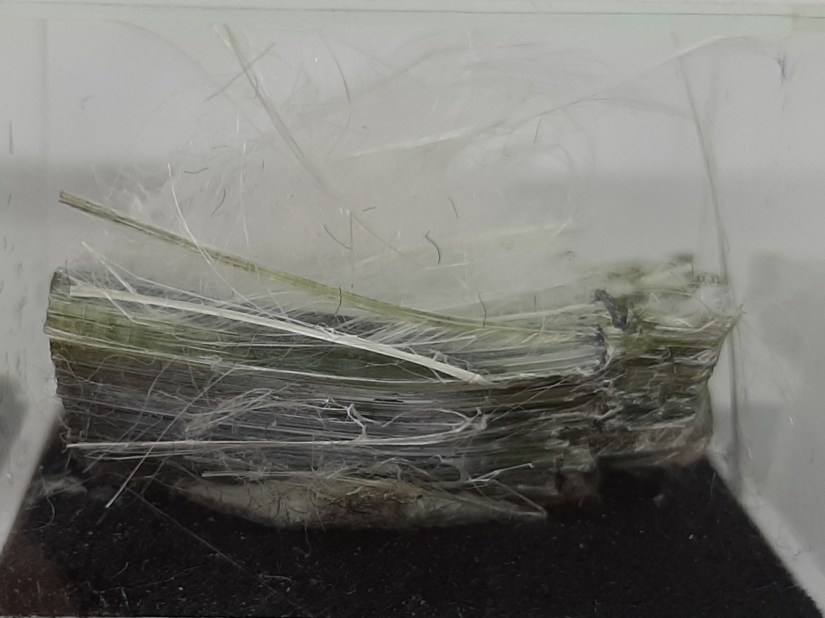

In short, asbestos must be handled with great caution. If you keep asbestos specimens in a collection, store them in sealed containers. When opening any container, keep your face turned away and avoid inhaling dust. Keep asbestos well out of the reach of children, and ensure all containers are clearly labelled as containing asbestos.

Most people won’t come across very many asbestos minerals, especially if you mainly collect polished pieces. However, there are two common stones that contain asbestos which you encounter fairly regularly. How dangerous are they?

Swiss opal

Swiss opal is a combination of chrysotile (white asbestos) and ‘serpentine’. Serpentine is a group of minerals, chrysotile being one of them. Other well known members of this group are lizardite and antigorite. Most stones that are being called serpentine or ‘serpentine jade’ are actually serpentinite, a type of rock that consists predominantly of serpentine minerals. Serpentinite can contain chrysotile, which is a type of asbestos. Asbestos in serpentine is mainly concentrated in clearly visible bands/layers. Outside these layers it can occur in very small neglectable quantities. These asbestos layers do not occur in all types of serpentinite.

One specific variety, dark green serpentinite with clear white layers of chrysotile is being marketed under the trade name ‘Swiss opal’. This name gives you no clue at all about the real contents of this stone. It is not from Switzerland and has nothing to do with opal. So the name doesn’t make any sense at all. Other trade names for this are ‘lizard skin jasper’ and ‘green zebra jasper’. Most sellers promise you that polished pieces of Swiss opal are harmless. That is not true. Asbestos cannot be polished, so these white layers will never become smooth and they can potentially lose fibers after polishing. Besides that… what if you drop the stone or it breaks? In the below photos you can clearly see the loose asbestos fibers in a damaged tumblestone. It does not matter whether this is polished or rough, it is asbestos, so it has to be handled with care and is not suitable for children.

Tiger’s eye

When people hear that the fibrous structure and the beautiful chatoyance effect in tiger’s eye effect come from asbestos, it can be quite alarming. But tiger’s eye is more than just asbestos. Tiger’s eye is the brown variety of blue hawk’s eye or falcon eye. Hawk’s eye is crocidolite in quartz. Tiger’s eye is the oxidised variant, which explains the brown colour. In the past, it was believed that hawk’s eye and tiger’s eye were quartz pseudomorphs after crocidolite. Nowadays, understanding has changed. It is now thought that it consists of crocidolite that developed cracks, allowing silica-rich water to penetrate, form quartz, and enable the crocidolite to grow within the quartz. This results in bands of intergrown quartz and crocidolite (source: Heaney & Fisher, 2003).

Overall, there is general agreement that hawk’s eye and tiger’s eye intergrown with quartz pose little to no risk, especially in polished form. Unfortunately, with hawk’s eye, very occasionally the intergrowth with quartz is incomplete, and raw specimens can contain loose asbestos fibres. With polished pieces, however, there is no need for concern: if there is no quartz present, hawk’s eye cannot be polished.